When Does “History” Begin?

I know that it’s been a while since I’ve posted anything – I’ve now let life get in the way of three different series that I’ve started on here. For now, I can’t fix that, but I trust that I’ll come back to each of those in the near future.

For today, I just wanted to make note of something I’ve noticed dozens of times, but haven’t really processed fully.

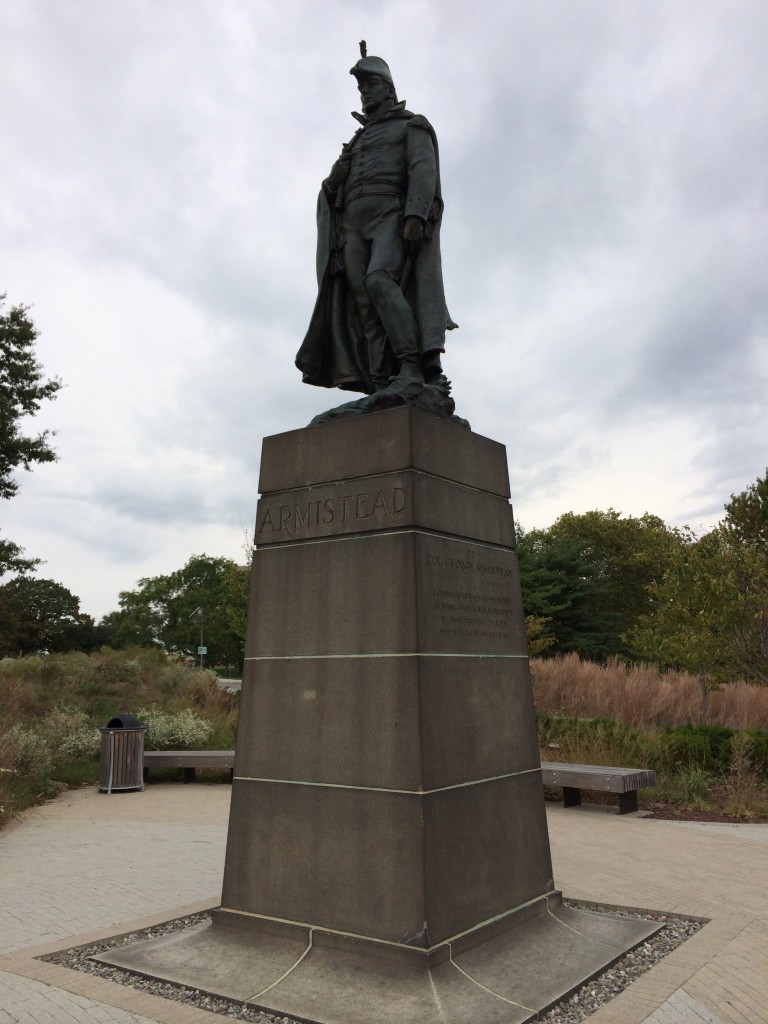

I met a few of my wife’s family members down at Fort McHenry today for a tour. While I was waiting for them to arrive, I wandered over to the George Armistead Monument near the parking lot.

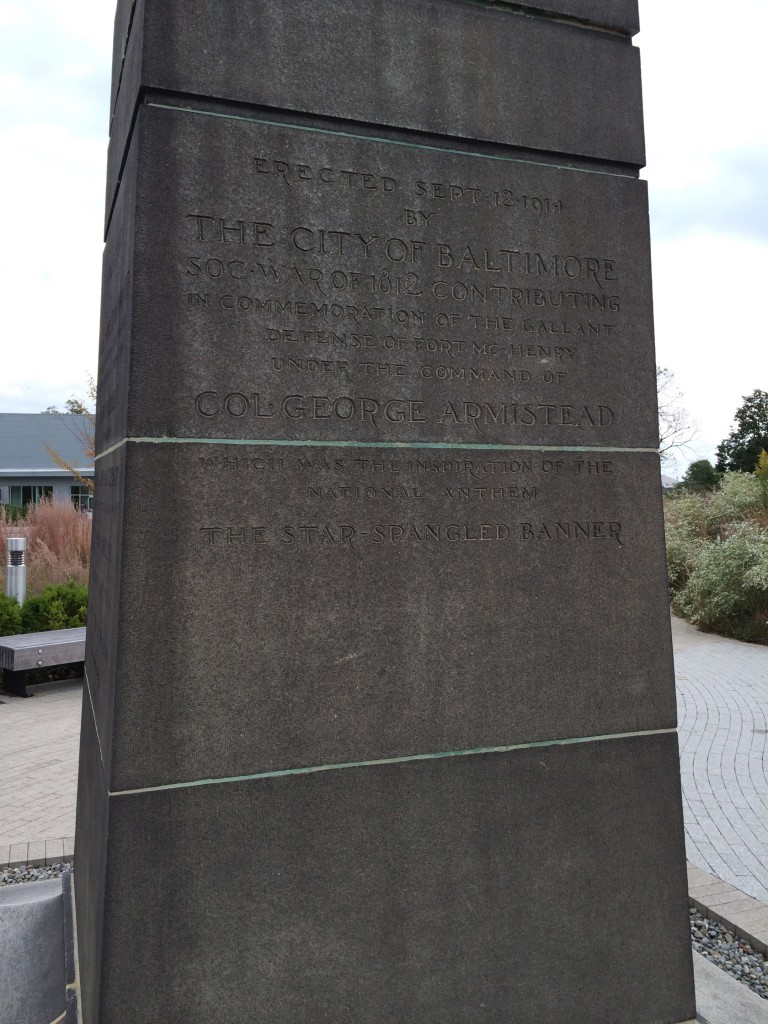

It’s a nice, simple monument. There’s a likeness of him, birth and death dates, and a line about why he was important. All the usual stuff you’d expect on a memorial for a man with a great role in history. The issue I want to explore comes in on “the back” of the pedestal:

There is more text on this monument that describes how, when, and by whom it was put in than there is to describe the thing it is actually memorializing. Like I said, I’ve seen this same type of thing on monuments dozens of times, and it always strikes me as being pretty narcissistic. As if the people who decided on the design and placement of the marker deserved equal praise and billing with the memorialized person or event!

The thing is, this is some useful information in some ways. Who and what a people choose to memorialize can tell you something about those people – George Armistead was obviously enough of a hero in Baltimore in 1914 that this commission decided they needed a sculpture of him. And you don’t have to do any further research to discover who the sculptor was. You can further infer that there was a big to-do made of the centennial celebrations of the Battle of Baltimore, what with a monument dedication and all. Maybe one of these commissioners was a relative of yours – a remote possibility to be sure, but something similar happened to my dad years ago at the Maryland Institute.

I guess what I’m saying is that there’s a place or time when this kind of thing stops being the grandstanding of politicians and influential businessmen, and becomes “history” that is worthy of study. Not so much of the event itself, but of how the event is portrayed, and by whom. “Meta-history” if you will, but history nonetheless.

Where is that line? I have a hard time deciding. 50 years? 100? A generation or two? Maybe when the day-to-day decisions of these politicians and notable citizens fade from our memory, and thus cease to have so much controversy associated with them? History is curved, after all. I suppose it’s up to the future viewers of the monuments to make that call for themselves.

There may be some merit to exploring the backs of the monuments, too.