Was Sickles Right?

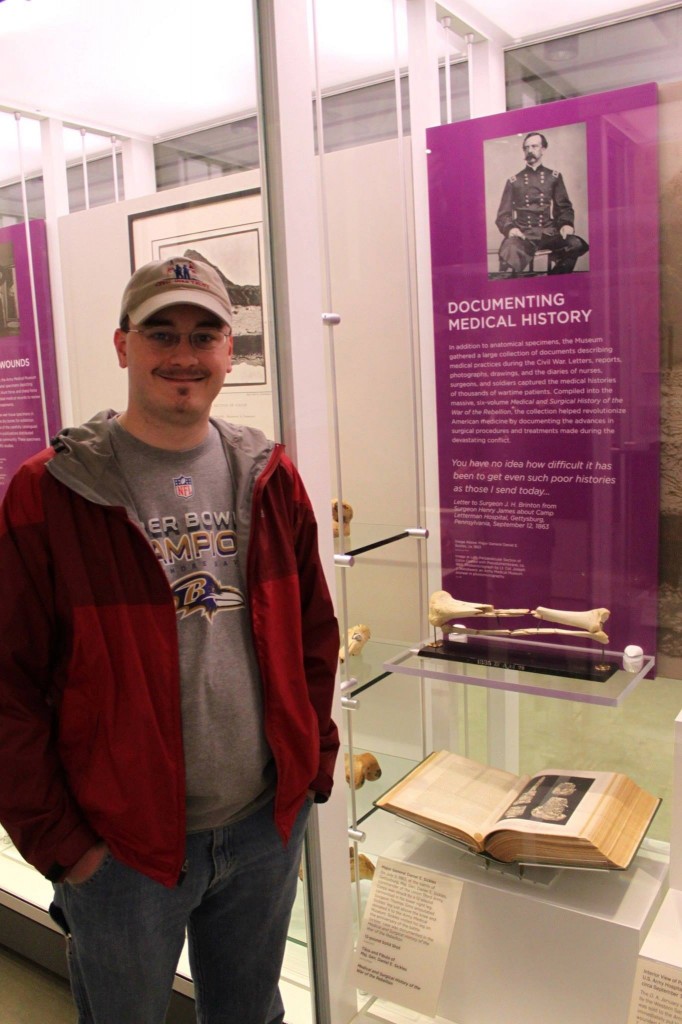

My brother Phil – a USMC Captain – took a trip up to Gettysburg with me last Friday. Phil’s interest in going was to see the field and analyze what happened there from the perspective of his modern Marine Corps infantry training. Of course, I thought it would be cool to see how a modern soldier goes through that process. It would be a learning experience for both of us.

It was a really great day (if not a little on the cold side). I took him through almost the whole tour. While we hit Culp’s Hill, we didn’t get to the East Cavalry or South Cavalry fields, and we tended to ignore the Confederate perspective, focusing instead on the Union defensive positions to get our views of the field.

The biggest surprise of the day was his reaction to Maj. General Daniel Sickles‘ part in the battle.

In the interest of full disclosure, I’m a fan of Sickles (as you could maybe tell). My thoughts prior to last week were more-or-less middle-of-the-road on his actions during the battle. I can see both sides of the argument, but I tend to lean in the pro-Sickles direction if I’m pressed. Obviously, I’m OK with the over-all outcome of the battle, and I find counterfactuals to be…difficult (to say the least). Even if they are fun, they’re a sloppy way to do historical analysis.

All that said, I did my best to be even-handed. On the drive up, I reminded Phil about Sickles’ murderous history, and his path to the army by way of political considerations rather than military acumen. As the highest-ranking non-West Pointer in the Army of the Potomac, he was the very definition of “black sheep”.

My character assassination prep work was all undone as soon as Phil set foot in the Peach Orchard. Instantly, he said that this is where he’d want to be. It was the same when we got out on Houck’s Ridge. He became more adamant as I explained how Sickles came to his decision to move. Let’s go through it.

The III Corps had arrived at Gettysburg the night of July 1, 1863 by way of the Emmitsburg Road. They would have passed right over the Peach Orchard on their way to the field. Coming down off of that terrain to take the position they did to the left of the II Corps must have felt strange. By the morning of July 2, Sickles was asking headquarters to clarify his orders as to the III Corps positioning. Was Sickles playing a game here?

The orders were to extend the II Corps line to the south, and occupy the position held by Brig. General Geary‘s division the night before. Does anyone know what position Geary’s division held? Sickles sure didn’t – Geary vacated the position and moved to Culp’s Hill at about 6am, and Sickles slept in until around 9am. So where was Geary? Where was Sickles supposed to end his line? Little Round Top.

While LRT is a nice piece of real estate, take a look at the rest of this proposed position. Have you ever ridden the line from LRT up to just before the Pennsylvania Monument with a critical eye? This was Sickles’ assigned position. It’s kind of a drive-through wasteland until you get up to United States Ave. There’s hardly any regiment markers along there, and NO cannons on display. Ever wonder why?

Next time you’re in Gettysburg, drive up to the VI Corps headquarters marker. Pull over to the right side of the road and park. Now look around. Where are you going to place a line in here? The open ground to the left (west) is rocky, marshy, and low-lying – generally unfit for troop deployments. It’s also got a great view of…those woods in front of you. You won’t see the enemy approaching. Placing your line on the small, tree-covered hill to the right (east) will affect your visibility even more, and that hill isn’t big enough to cover the whole sector effectively anyway. And there’s NO WAY to use artillery anywhere around here because of all the woods.

North of United States Ave. it isn’t much better. At least you can place artillery here (and the NPS has pieces out to help your imagination), but as you look west, you can see how the ridge that the Emmitsburg Road is on (including the part that contains a certain Peach Orchard) absolutely OWNS (as Phil would say) this line. With enemy artillery placed there, and a concerted infantry effort to go along with it, any troops in this position could be dislodged. It’s NOT a very good place to be.

I think this is why Sickles was confused the morning of July 2. “This is my position? THIS? Are you for real right now?” It was such a bad placement that it couldn’t possibly be what was intended. He HAD to be confused.

Sickles would much rather be up on that Peach Orchard and along the Emmitsburg Road. It’s much higher, open ground. He’d have no problem employing his artillery effectively. It’s obvious to anyone who really looks at it that this is the better position, right?

By late morning, Sickles is up at headquarters lobbying for someone to come help him deploy his corps. General Meade was too busy to have a look. Besides, if the Confederates attacked, it would probably be from the north – where they were known to be located. General Warren, the Chief Topographical Engineer, couldn’t be spared to examine the position either. Since the main concern expressed by Sickles was related to placing his guns, General Hunt, the Chief of Artillery, was allowed to go to the left flank and advise General Sickles.

Hunt agreed that Sickles’ position was horrible for artillery. There were no good options. Sickles asks Hunt to ride out to the Peach Orchard – his preferred position – to have a look.

Immediately Hunt realized – like my brother 150 years later – that this ground was commanding. Artillery placement would be easy and effective out here. Sensing Sickles’ enthusiasm, Hunt was quick to remind the III Corps commander that, while he agreed with the assessment of the terrain, he could not authorize a troop movement. Of course, he did give a final piece of advice: If he were to make such a move, he’d want to know what’s going on in the woods over on Seminary Ridge first. Sickles agreed and sent Hiram Berdan‘s Sharpshooters on a recon mission.

Of course, Berdan finds Confederates – the right flank of Wilcox‘s brigade. This is enough evidence for Sickles to believe that an attacking force was massing on his front. He decided to make his move, and the rest is history.

The move was not without problems, though. Sickles’ small III Corps didn’t really have enough men to cover his intended line effectively. He was now trying to cover nearly twice the frontage that he had been originally assigned – from the Codori Farm down to Devil’s Den. He tried to compensate for this by using artillery to hold the gap between the Peach Orchard and Rose’s Woods. Sickles feels like he doesn’t have much of a choice though. He can’t force other units to come to his aid, and headquarters doesn’t seem too concerned with what may be happening on the left flank.

By the time General Meade starts paying attention, it’s too late. The Confederate attack has already begun, and Meade feels like his only choice is to commit resources from the V and II Corps to try and shore-up the position.

Of course, we know that this was not enough, and the failure of that line to hold is attributed by some people to Sickles’ incompetence. After all, he didn’t have enough men to cover the line. Obviously, the fact that he doesn’t have the proper resources doesn’t mean that the position is a bad one. Could he have done a better job communicating the issues he was seeing to headquarters, and more forcefully requesting reinforcements? Sure. Could Meade have not ignored the concerns of his political general, and taken a closer look at the positioning of his entire army? Absolutely.

The two military virtues that Phil really saw Sickles living out were making decentralized command decisions, and being offensive-minded.

While many people will fault Sickles for disobeying orders (or at least being loose with their interpretation), my brother argues that it’s a positive thing. Sickles knew things that Meade didn’t, and rather than wait for permission, he took initiative and did what he could to counter the threat.

In taking his action, even in a defensive posture, Sickles was thinking aggressively. He was looking for a better position for his troops. He was actively seeking out threats to his front, and looking to deprive the enemy of the elements of surprise and superior terrain.

Yes – the III Corps took about 40% casualties on July 2, but with his line placed in the horrible position it was “supposed to be in”, do we really know that things would have turned out any better? Sickles’ move definitely caused the Confederates to change their attack plan, and delayed their advance significantly.

Like I said before, it’s very hard to do counterfactuals. You can never really know the answers to all the “what ifs”, but I think that my brother is right. Being on that ground you can tell that the Emmitsburg Road / Peach Orchard / Devil’s Den line is a much better piece of terrain than the marshy mess that the III Corps began the day with. And who knows – if Meade had been involved in making the move, and provided an adequate number of troops in the first place (instead of as last-minute reinforcements thrown in almost haphazardly), could that line have held against the single wave of Confederate attacks that came against it? I think it stood a pretty good chance.

We’ll never really know, and that’s part of the fun.