Notes on Pickett’s Charge

Today I realized that I have yet to post anything on the blog during this calendar year, and it’s already August! Sometimes, our hobbies need to take a backseat to real life, I suppose.

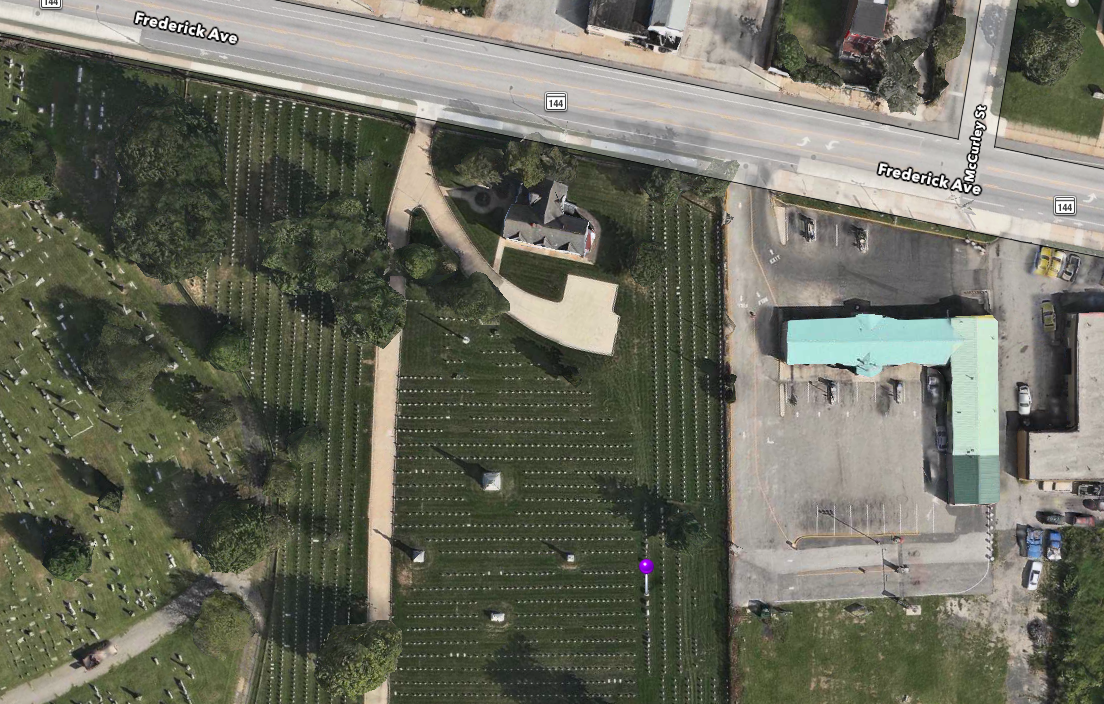

Back in May, I took my annual trip to Gettysburg for my church’s men’s retreat. Once again, it was my pleasure to lead a tour of the battlefield for many of the other men in attendance. Rather than an overview of the entire battle, this year I decided to focus on the most well-known portion of the battle: the climactic Confederate assault known as Pickett’s Charge.

At least, it seems well-known. There are so many little stories that come together to form the larger story. My research in preparation for the tour led me to explore the impact of the Bliss Farm action on the charge and I’ve come to believe that this often overlooked “small unit action” had a tremendous impact on the outcome of the attack. But I plan to post more about that later.

For now, let me share some of the notes that I took during the early stages of my research. These things jumped out at me as interesting details that contributed to the overall story:

1) Longstreet and A.P. Hill Didn’t Get Along.

Earlier in the war, following the Seven Days Battles, a Richmond newspaper published a particularly glowing account of A.P. Hill‘s combat prowess at the Battle of Frayser’s Farm. This really offended Longstreet who felt that he (and his other men, I suppose) had fought just as hard as Hill in the same action. So Longstreet contacted a rival newspaper and convinced them to publish a rebuttal downplaying Hill’s role.

The conflict remained unresolved, however. Longstreet continued to hold the grudge against Hill – even going so far as to have him arrested for the relatively minor offense of not turning in an after-action report in a timely fashion a few months later. General Lee had to personally step in when Hill took the step of challenging his commander to a duel.

As Longstreet’s character notes in The Movie, of the three divisions involved in “Pickett’s Charge”, only Pickett’s belonged to Longstreet’s Corps. The other two belonged to A.P. Hill’s Corps. If Hill wasn’t going to lead the attack, you’d think that he would at least have a part in planning and implementing it. But there is no evidence of any coordination (or even communication) between Hill and Longstreet on July 3, 1863. Was this the continuation of the year-old tension between these two men? What if the upper levels of the Confederate command hadn’t been consumed by such petty differences?

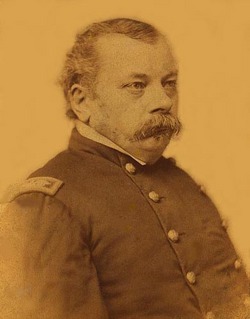

2) John Gibbon Had Interesting Connections

Brig. General John Gibbon, commanding the 2nd Division of the Union II Corps at Gettysburg (even taking over command of the Corps at one point during the battle) was born in Philadelphia, but spent much of this childhood in Charlotte, NC where his father worked for the U.S. Mint and owned slaves. His wife, Fannie, was a Baltimore girl, adding to his local interest for me.

While much has been said of the close relationship between Generals Hancock and Armistead, and how tragic their meeting in battle was, they were certainly not the only men who shared such a story. General Gibbon was facing down his own family: J. Johnston Pettigrew, commanding one of the “other” Confederate divisions in the attack, was his cousin.

3) The Copse of Trees Was Quite Different

The famous target of the attack – the Copse of Trees – is not the same today as it was in the summer of 1863. For one thing, the trees themselves were much smaller; described as not being much more than 2″ in diameter.

The grove was also larger. Despite the impression left by the modern fenced-in area, the trees actually extended farther to the west – almost to the stone wall. Members of the 69th PA were able to shelter in those trees during the repulse.

4) The Effects of the Barrage Were Different

By and large, the Confederate artillery barrage caused tremendous damage and casualties among the Union artillery. The infantry units were virtually unscathed during the run-up to the assault.

Across the valley, the Confederate infantry sheltering in the tree line took a pounding from the Union counter-fire. The Confederate artillery positions hardly took any damage (though their ordinance replenishment operations ran into major problems).

5) Overall Communication / Coordination Was Horrible

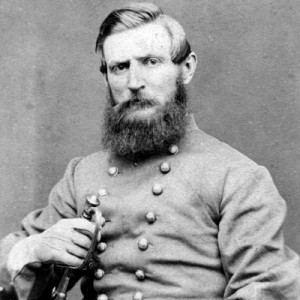

While the morning was spent planning the attack, it seems like the details didn’t make it into the hands of the commanders on the ground who were to actually bring the assault into action. Pettigrew seemingly never got the order to step off. He saw Pickett’s troops moving forward and decided on his own that it must be time to go.

Even worse, his left-most brigades, under Joseph Davis, and John Brockenbrough, even missed out on Pettigrew’s order to begin. It took them at least another five minutes to get their units on the march. An already long-shot attack started with disjointed, un-coordinated lines from the very beginning.

6) There Were Lots of Medals of Honor

To date, 25 Medals of Honor have been given to Union troops and officers for actions during Pickett’s Charge (the most recent just last year on November 6, 2014).

While there were most definitely many acts of valor committed that day, the original requirements for the Medal of Honor were not what they are today. The US military had no other combat decorations, so any act that was felt to be deserving of recognition warranted a Medal of Honor, so there were more given than modern readers may think are deserved. For example, more than half – 15 of the 25 – Medals of Honor were given for actions surrounding the capture or mere collection of a dropped Confederate flag.

In addition, it was very rare for the Medal of Honor to be given posthumously back then. Only about 3% of the 1,522 given for actions during the Civil War were given to men who were dead at the time of the award. With that, many obviously deserving acts went unrecognized – part of the reason that so many of us are relieved that 1LT Cushing finally got his due, even if it was over 151 years too late.