Great News from Gettysburg!

The Cyclorama building is GONE!

AND the 11th Massachusetts monument is finally back to normal (after 7+ years).

Things are looking up for the 150th anniversary this summer.

The Cyclorama building is GONE!

AND the 11th Massachusetts monument is finally back to normal (after 7+ years).

Things are looking up for the 150th anniversary this summer.

My wife, son, in-laws and I ended up taking our trip on Sunday. It was a really nice time.

We left the Baltimore area around 10am, and made it to Fredericksburg a little before noon. Our first stop was on the near side of the river in Falmouth, at Chatham Manor – an old plantation mansion dating back to the 1770s, currently owned by the NPS. Washington, Jefferson, and Lincoln all visited this house, and it’s apparently the only house that can boast of having hosted each of those men as guests at one time or another. Robert E. Lee also met his wife here. There were a few very grand old trees planted in the 1810s that made for popular photo subjects for our group. There were also plenty of interesting little architectural details on the house and grounds that attracted my wife’s camera, too. I was more interested in this guy, though:

Here’s another shot so that you can get some context. I’m just a little under 6 feet tall:

Since my usual battlefield hangouts are Gettysburg and Antietam, I only ever see the smaller field pieces – these big siege guns are a treat to behold. They aren’t the only ones down there, either – the Confederate line has a few 30-pounder Parrots on display. Unfortunately, the markings on the 2 guns here at Chatham are almost totally unreadable. Either they have been worn off over time, or they’ve been painted-over a few too many times – perhaps both. It’s a shame because I’d love to know more about where these came from. Anybody have a good resource for that?

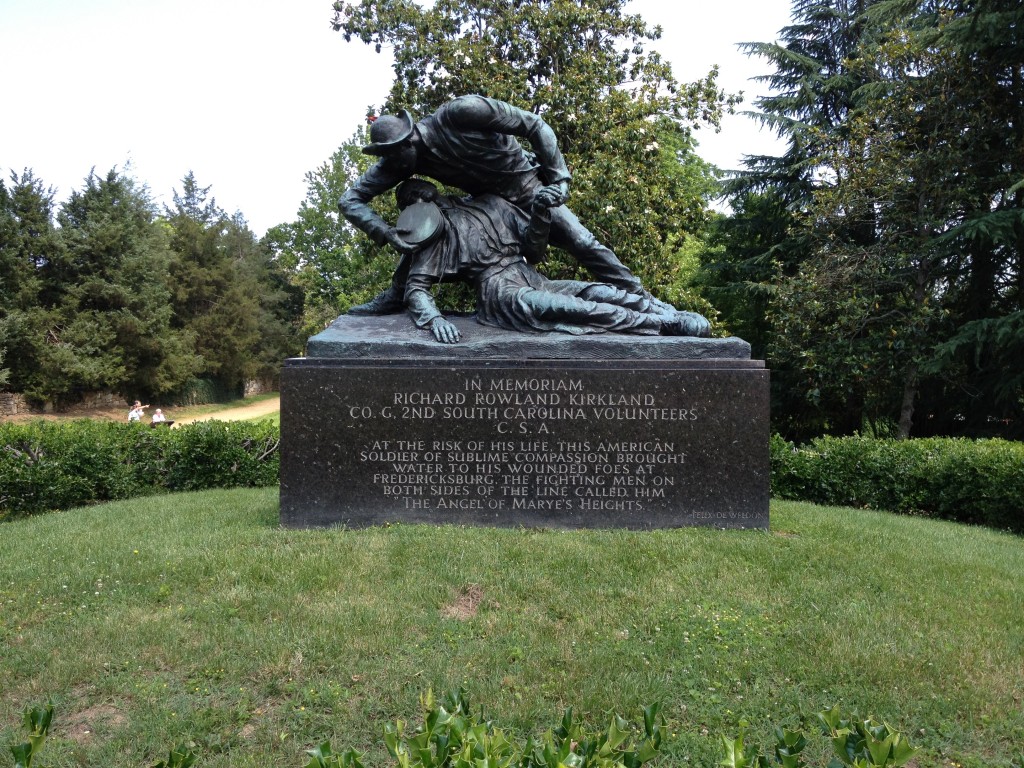

After Chatham, we crossed the Rappahannock (much more successfully than Ambrose Burnside and the Army of the Potomac did in 1862) and found our way through town to the Sunken Road section of the Fredericksburg battlefield. We walked along the stone wall, imagining the scene of brutal killing that took place a little more than 150 years ago in what is now a quiet neighborhood. Finally, we came to the original inspiration for the trip, the Kirkland Monument:

Reading the story of Richard R. Kirkland and seeing the monument was a touching moment for the group. A small sign of humanity in the midst of all the murderous destruction.

After the short walk back to the car, we drove down the rest of the Confederate line to the end at Prospect Hill, just so that everyone could get an idea of the scope of this battle and see the Confederate earthworks along the way.

We grabbed a quick late lunch outside of town and then went out to Chancellorsville. This time, we did a relatively quick driving tour of the field. We oriented ourselves at the visitor’s center (and saw the spot where Jackson was wounded). From there, we drove along the Confederate line to the Lee-Jackson Bivouac and Catherine’s Furnace so that I could explain the famous flank march. To get the Union perspective, we drove up to Hazel Grove (where I engaged in a little more artillery-nerdery) and then out the Plank road to the right flank of the Union line, where I explained Jackson’s surprise attack.

By then, it was getting a little late, and we had to get the baby home for bed, so we hit the road back to Baltimore. Everyone seemed to have had a good time (even John was well-behaved), and I think we all learned something and had new experiences – the hallmarks of a successful historical day trip.

The last Civil War adventure that we had with this part of the family was going out to the Antietam battlefield. Chronologically, the next battle in the east was Fredericksburg, then Chancellorsville – both of which we just covered yesterday. Now, the stage was set for Lee’s second invasion of the north. It’s pretty obvious what needs to happen now: I think when my niece and nephew come up for a visit in the summer, we’ll have to head to Gettysburg to keep the timeline going. That’s always a fun day.

I went over to my in-laws one night this week to help my father-in-law move some computer equipment around. While I was there, my mother-in-law was telling me about a conversation she had with someone she met at a conference. The guy was from Virginia (she thought Petersburg) and he was telling her about a monument to a soldier who went across the lines to render aid to some of his wounded enemies. I think they were talking about this one:

I mentioned that I think that monument is at Fredericksburg, not Petersburg (there may be a similar monument at Petersburg – I’ve never been there), and with Fredericksburg being only 2 hours away, it’s easy to do as a day trip.

So on Sunday, I’ll be taking my wife, son, mother-in-law, and father-in-law down to Fredericksburg. So far as I know, it will be their first visit. I’ve only ever been once, and I went through pretty quickly as I was trying to do the entire Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park in one day. This time, I’ll not only have other people with me, but they’re people who aren’t quite as nerdy as I am about this stuff. I’d like to slow down a little. Chatham Manor is on the agenda (I skipped that side of the river last time), and I’ll probably leave out the southern end of the Fredericksburg field – as cool as I think Lee’s Hill is, I’m not sure that the group will want to make that climb. The main things will be finding cool views, seeing the sunken road, and getting a picture with that monument.

Depending on how the day goes, I might try to convince the group to go out west and see Chancellorsville. Since my big interest lies in Gettysburg, it would be nice to show the family the whole flow of that part of the war: Fredericksburg leading into Chancellorsville, and that battle setting the stage for the Gettysburg campaign. I think the biggest struggle will be the fact that none of these fields is as well-monumented as Gettysburg – there’s a bit more imagination needed to see what was going on. If we go, it’ll probably be a quick driving tour, with this (of course) being the critical stop:

It would also be nice to get a closer look at the artillery pieces up on Hazel Grove. I didn’t pay enough attention to the details on them last time.

I spent tonight (and will probably spend some time tomorrow night) brushing up on Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville so that I’m sure that I understand enough of the details that I can give a good overview and answer questions. I’ve focused on Gettysburg for so long, and gotten so deep there, that I really feel like I should branch out a little more.

Hopefully, everything will be smooth and we’ll all have a good time. I’ll probably write up a review once we get back.

This is a continuation of a series of posts that are intended to be shorter, more understandable versions of the Federalist Papers. This post deals with Federalist #19, the original text of which can be read here: http://thomas.loc.gov/home/histdox/fed_19.html

Originally published December 8, 1787 by “Publius” – who was in this case, James Madison (possibly with some help from Alexander Hamilton).

The ancient governments I described in the last article aren’t the only examples that would be useful to us. There are other similar ones existing today that are worth a look. For starters, Germany.

What is now Germany has been occupied by many different peoples in the past. Under Charlemagne, France controlled Germany – until Charlemagne’s heirs broke up his empire. When that happened, Germany became a free-standing state because the local feudal overlords gradually took more and more power. The Empire of France was powerless to stop it. Small wars broke out between the local rivals for land and power, until an Austrian emperor rose.

With this style of feudalism being much like a confederacy already, it isn’t surprising that the current Germanic empire is federal in nature. There is a legislature (called a diet) which is representative of the “states”, and holds much of the power. The executive (an emperor) holds a veto on the acts of the diet. There is also a dual judiciary in the form of the Imperial Chamber and the Aulic Council.

The emperor has a lot of power. He is the only person who can propose measures to the legislature, and can veto what they come up with. He picks the ambassadors, grants titles of nobility, appoints replacement legislators in the event of a vacancy, creates universities, collects and spends taxes, and is ultimately responsible for the overall public safety. In his capacity as emperor, he doesn’t get any land or money, but he is still extremely powerful.

You’re probably thinking that there is so much power in the federal government of Germany, that it must be an exception to the rule. But this isn’t the case. The core principle here is that the empire is made up of sovereign states, and the federal government affects only those states. This means (like we discussed before) that the government can’t effectively control the states, can’t protect against foreign threats, and deals with constant internal squabbling.

Throughout it’s history, Germany has had wars between the emperor and the leaders of the states, and between the leaders of the states and the states themselves. There has been disregard for the rule of law, and the weak have been preyed-upon. Foreigners have frequently invaded. Requests for soldiers and funding have been ignored (with many failed and bloody attempts to enforce those requests). In general, the government has been inept, confused, and utterly terrible.

There was a time when the emperor was at war against half of his own country. He barely escaped an attempted capture, and on a few occasions was personally beaten by one of his own princes. There have also been too many wars between the German states themselves to count. After one such war (in which Sweden joined with many of those states against the emperor) a peace that was negotiated by foreigners was enshrined in Germany’s constitution!

The empire can’t even defend against foreign threats. There is so much infighting among the member states that they can’t join together before they are already invaded and winter has come.

Because of all this, they find it essential to have a small army at the ready at all times, but it is not well maintained and its soldiers are only paid every now and then.

Since this obviously wasn’t working out well, they decided to try splitting the empire into 9 or 10 districts. The rulers of these districts were to ensure that the laws were executed (even by military means), but this only illustrated the real problem: these smaller governments were just echoes of the original one. They either ended up not getting the job done, or doing it in the bloodiest way imaginable. In some cases, these districts are entirely composed of the troublemaker states (which was the problem they were supposed to solve).

It’s easy to judge the effectiveness of this system. A Catholic leader in Donawerth tried to hold a procession and a riot broke out. Martial law was declared, and the Duke of Bavaria tried to enforce it. Arriving with 10,000 soldiers, his true intentions became clear – he wanted to take the territory for himself (disarming the citizenry in the process).

So why hasn’t their government totally failed after this long? The states’ individual weakness – that’s why. Some are weak within the empire, and even the strongest of the states are weak when compared to their foreign neighbors. The emperor also has a reputation to uphold, and wields a lot of power by keeping these separate domains held together (however strained that hold is). This makes for a weak union, but as time goes on and people become more set in their ways, it becomes harder to change. Even if they were to make the empire stronger with a better-designed government, what makes you think the foreign powers surrounding the empire would allow that to happen? They will do whatever they can to keep the individual states warring amongst themselves, and thus weak as a whole.

If you’re looking for more examples of central governments controlling only member states (and not individual citizens) you might think of Poland. Their government is constantly having problems. It can neither govern nor defend itself, and is always at the mercy of the much stronger countries around it (who recently took by force over 1/3 of it’s land and population).

Some people think that the Swiss government is a stable confederacy, but the loose union of the cantons there doesn’t really qualify as one. There is no common treasury, army, monetary system, court system – nothing.

The only things binding them are geography, their own weakness compared to their neighbors, their shared peaceful culture, an inter-dependence upon their lands, the need for help with defeating internal rebellions, and the need to resolve conflict among themselves. They form ad-hoc courts from among the other cantons when needed, and choose a chief judge, or umpire if there is a split vote. This didn’t work out so well when the Duke of Savoy decided to make himself the mediator, and used military force to do it.

All of this evidence proves my point. Anytime the states within this “confederacy” had serious differences come up, the system broke down. There have been multiple wars over religion among the Swiss, and they now have two separate cantons (Catholic and Protestant), with totally separate legislatures. Their federal legislature is now almost totally powerless.

Of course, that wasn’t the only problem to come out of the big Catholic / Protestant split: the two sides are now allied with different foreign powers.

I’m extremely sad that I’m going to have to miss this. Unfortunately, my son is too young to tag along, and I won’t be able to arrange childcare for that day since my wife has to work.

I’ve been to Brandy Station once with my wife for about an hour. We were coming home from spending a nice long weekend in Charlottesville, VA and I noticed that the battlefield was right along our route. Knowing what a nerd I am for the Gettysburg campaign, she allowed me to stop. Being a late afternoon in rural Virginia, we had the field all to ourselves.

It isn’t exactly what her idea of a battlefield is. There are no monuments. There are only a few informational signs placed by the Civil War Trust along a walking trail through rolling fields and on hills. Hard as it may be to believe today, this peaceful site was the setting for the largest cavalry battle to ever take place in the western hemisphere – a fitting start to the campaign that would culminate in the war’s bloodiest fight.

Reading about the battle is one thing. But to really understand what happened, you just have to see the ground for yourself. If you can make it, I highly recommend that you take part in this tour – it’s free for goodness’ sake (and send me pictures!)

This is a continuation of a series of posts that are intended to be shorter, more understandable versions of the Federalist Papers. This post deals with Federalist #18, the original text of which can be read here: http://thomas.loc.gov/home/histdox/fed_18.html

Originally published December 7, 1787 by “Publius” – who was in this case, James Madison (possibly with some help from Alexander Hamilton).

Of all the ancient confederacies that we know about, the old Greek “council of neighbors” seems to be the most like our current American system.

Each city-state kept its own government, and all had an equal voice in federal matters. The central government took care of whatever it thought was in the common interest of the members: declaring and running wars, acting as a court of last resort, putting down rebellions, and bringing other city-states into the fold. They ran a state-controlled religion (including courts associated with the temples). The central government was sworn to protect the city-states, and to punish both rebels and heathens.

This certainly seems like enough power, doesn’t it? But this amounts to more power than we gave our government in the Articles of Confederation. That ancient government controlled the religion of the people, and was supposed to use force against the member city-states when they got out-of-line.

Of course, it didn’t work out that way. These powers ended up being executed by officers appointed by the city-states themselves, so they were never really used to their full extent. The more powerful city-states weren’t kept in-line, and merely converted the federal government into one that served their interests. Athens’ domination of ancient Greece illustrates this pretty well.

More often than not, the officers of the more powerful city-states strong-armed those of the weaker city-states into going along with whatever the stronger states wanted. The more powerful side, not necessarily the right side, won out.

Even when fighting wars with Persia and Macedonia, the city-states didn’t work together, and instead many even worked with the enemy! When not at war, the states squabbled with each other constantly.

For example, after the war against Xerxes, the Lacedaemonians tried to kick out all the traitor city-states, but the Athenians blocked the attempt because it would leave them at a power disparity within the central government. This one example shows how inefficient and unjust this union was. Even though the smaller states were supposed to have an equal say, they ended up being co-opted by the larger, more powerful states in practice.

If the ancient Greeks had really been thinking about it, they would have used the peaceful periods to make their government work better. Instead, the larger city-states (like Athens and Sparta) became power-hungry and ended up inflicting more damage than Xerxes had managed to. All that mistrust and anger culminated in the Peloponnesian war, destroying the government in the process.

Weak governments always end up suffering from internal conflict when they aren’t at war. This civil unrest naturally invites foreigners to try to disrupt things. Philip of Macedon gained control of Greece by pitting the city-states against each other over minor conflicts, and allying himself with the weaker side. It then wasn’t difficult for him to bribe his way into a leading position in the federal government.

Had their government been better-constructed and more unified, the Greeks may have avoided this sequence of events, and later been a more effective check against the power of the Romans.

The Achaean league also serves as a good example for us.

This was a much tighter and well-designed union. Even though they had similar problems, they didn’t really deserve them.

Each city-state maintained its own sovereignty, elected its own leaders, and was equally-represented at the federal level. Their central government exclusively handled declarations of war, diplomatic relations (including all treaties), and the election of a central executive called a praetor. He handled all military matters, and ran the government when the full senate wasn’t in session. Originally, they used 2 praetors, but found having only 1 to be better.

The city-states had a common set of weights and measures, used the same money, and had identical laws. We aren’t sure how much influence the federal government had in this area, but we know that when new members came on, they immediately started using the laws of the pre-existing city-states. This is the major difference between their system and that of the Athenians and Spartans.

It’s a shame that we don’t have better records of how the Achaean government actually operated. If we had more information on the inner workings of their system, it would enlighten all our discussions about how federal governments ought to work.

What we do know though, is that there was much more peace and justice, and far less squabbling in the Achaean league than in the other Greek governments where the city-states retained all the powers. As the Abbe Mably observed, there were fewer problems in the Achaean republic BECAUSE IT WAS THERE TEMPERED BY THE GENERAL AUTHORITY AND LAWS OF THE CONFEDERACY.

Of course, it was not a totally perfect set up. You can see that by the way the government ended up dissolving.

Originally, the Achaeans weren’t a big player in Greece, but once the Amphictyonic confederacy fell to the Macedonians, it wasn’t long before that foreign influence tried to break them up, too. Some were actually invaded, others were eroded from within through political corruption. The desire for liberty was awakened by these events, and eventually came close to uniting all of Greece under the Achaean system. The Athenians and Spartans, worried about maintaining their own power, put a stop to this though. While the Achaeans were trying to form an alliance with the Egyptians and Syrians, the Spartans attacked and spoiled the plan.

So the Achaeans were in a bad spot: they either needed to give in to the Spartans, or try to ally with the Macedonians. They choose Macedonia (who was only too happy to “help”). They sent an army to defeat the Spartans and eventually occupy the Achaean republic. The Achaeans tried to remove the Macedonian occupiers by allying with the other Greek states, but this wasn’t enough – they needed foreign help again, and this time they turned to the Romans who came in and did the same thing that the Macedonians had just done. The Romans fostered animosity between the Greek city-states, and convinced each that they should be totally sovereign. This led to the total destruction of the last great hope for a free Greece.

I’ve explained all of this seemingly unimportant history because it serves as a lesson – not just about the makeup of these ancient governments, but that it is much more likely for a federal system to fail because of dissent among its members, than by a tyrannical leader in charge of it.