My Connection to the Great Fire

The roots of the Skillman family in the Baltimore area go back for several generations. In a way, my immediate family may not have learned about those roots had it not been for the events surrounding the Great Baltimore Fire that I wrote about yesterday.

Today, I want to tell that story.

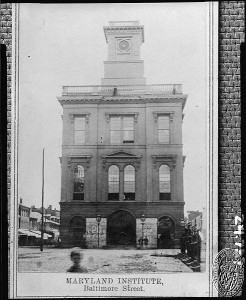

One of the buildings in Baltimore’s downtown business district back in the days before the fire was the Maryland Institute for the Promotion of the Mechanic Arts (which later became the Maryland Institute College of Art). Though the institution had been started in 1825, it had always rented space to hold its classes. The city block-sized building located between Baltimore and Water Streets, along the Jones Falls (the current site of the Port Discovery Children’s Museum), was constructed in 1851 and was the first structure that was purpose-built for the school.

In those days, the Maryland Institute was kind of half art school, half vo-tech. Courses in mechanics, chemistry, and drafting were taught alongside painting, sculpture, and music. There were different schools within the school, with night classes offered so that working people could improve their skills and get better jobs.

The building itself was quite spectacular. The bottom floor was a city market and the institute used the two upstairs floors. Along with classrooms and studios, there was a large meeting hall – one of the largest in the State of Maryland at the time – that was also used for public events. In fact, both the Whigs and the Democrats used the space for their party conventions in 1852.

The structure was in continuous use from the time it opened in 1851 until the very early morning of February 8, 1904 when the Great Baltimore Fire spread east toward the Jones Falls.

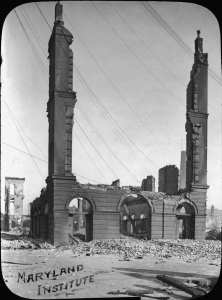

Being a relatively tall building for that part of town, embers that were blowing across town in the easterly wind hit the structure, and it soon caught fire – an isolated blaze at first that quickly spread to other buildings as firefighters were now facing a two-front battle.

No one knew it at the time of course, but the inferno was still more than 12 hours away from being under even moderate control. The Maryland Institute building didn’t stand a chance. Barely a shell remained once the fires were all totally extinguished a few days later.

Obviously, the institution has survived to the present day, and has morphed into a more pure fine art and design school. It’s also nowhere near the Inner Harbor anymore – its buildings now exist in the Mount Royal / Bolton Hill area. So what happened?

In the wake of the tragedy, the State of Maryland along with some wealthy benefactors and local business leaders, started looking for a way to rebuild. The mechanical and design skills that were taught at the school were extremely valuable to the local economy – especially when you consider the amount of re-building that a large part of the city was about to go through.

A plan to split the campus was devised. One piece of land in the Bolton Hill area was donated by Michael Jenkins to use as the site of a new building. Opened in 1908, this became (and remains today) MICA’s Main Building – housing the fine arts programs and even the first art museum in Baltimore. Another market building was constructed by the city at the original downtown site, and the institute’s drafting school would remain there – at least for a while.

So now, let’s fast-forward a few decades.

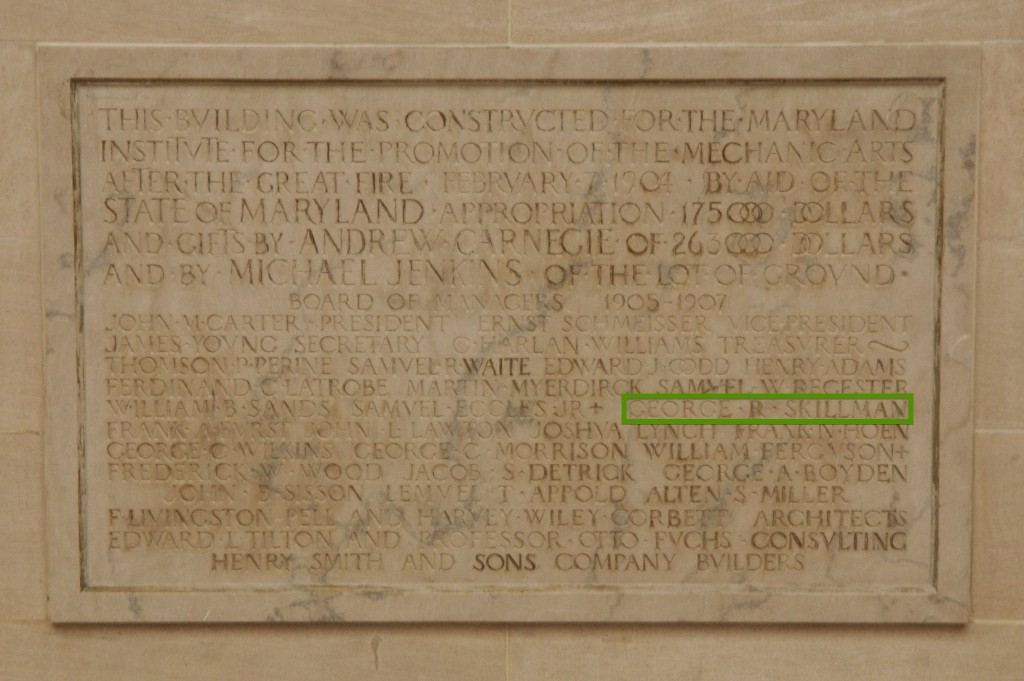

In the fall of 1977, my dad – George R. Skillman – started taking classes at the Maryland Institute College of Art. He’d always had an interest in history and architecture and those two subjects came together pretty perfectly in the aftermath of the Great Baltimore Fire. He had learned that MICA had been destroyed in the fire, and that the school he was attending was on the rebuilt campus. One day, his curiosity about that history led him to examine the dedication plaque for MICA’s Main Building.

The monument tells of the people who made the new building possible. Along with the monetary contributions of the State of Maryland and Andrew Carnegie, and the donation of the plot of land by Michael Jenkins, the school’s 1905-1907 Board of Managers – the men who oversaw the rebuilding process – were listed. Imagine how shocked my dad was to discover that his own name – complete with his middle initial – was there, carved into the wall:

Of course, this was obviously not referring to my dad. In 1908, his own father was still 13 years from being born. Who was this guy who had his name?

The accidental discovery spurred my dad to take an interest in our family tree. He started talking to relatives who had done research, and started to collect family records – a task that wasn’t as easy then as it is today. I’ve definitely benefitted from the stuff he found, and have also done some work to expand on it.

It turns out that this George R. Skillman wasn’t just a relative of ours, he was an ancestor: my great-great-great-grandfather. My dad is, at least indirectly, named for him. We don’t know as much about this forefather as we’d like to, but the few things that we know are pretty cool. He was the owner of a string of bakeries, and the inventor of a machine for making crackers. We’ve visited his gravesite, and the site of his largest bakery. We have some artifacts from his life – specifically some letterhead from his company. We also know that he must have done pretty well for himself to have served on the Board of Managers for such a large institution. My guess from looking at Census records is that the Civil War helped grow his business quite a bit.

My theme lately seems to be that history is all around us. I really believe that’s true. Deeply personal discoveries are there to be made if you keep your eyes open for them. Who knows? You may even find your name carved in stone somewhere.

Nice. When I was attending the Institute, I went to the library one day, which is down in the Mt Royal Station building on the second floor. There I met an old librarian (she was probably very very close to retiring). When she saw my student ID, she mentioned “George R.” There’s not much I remember about that conversation but I remember having it. It was a few years later that I was introduced to Betty Anne Daley, a distant relative living with her husband Kenneth in western Howard County, who made a big fuss over having a “George R.” present and proudly took me into her living room during a family reunion to show me an armoire that had belonged to “George R.” and had been acquired in his estate sale.

It was nearly as facsinating a discovery as fatherhood.