Fort Delaware

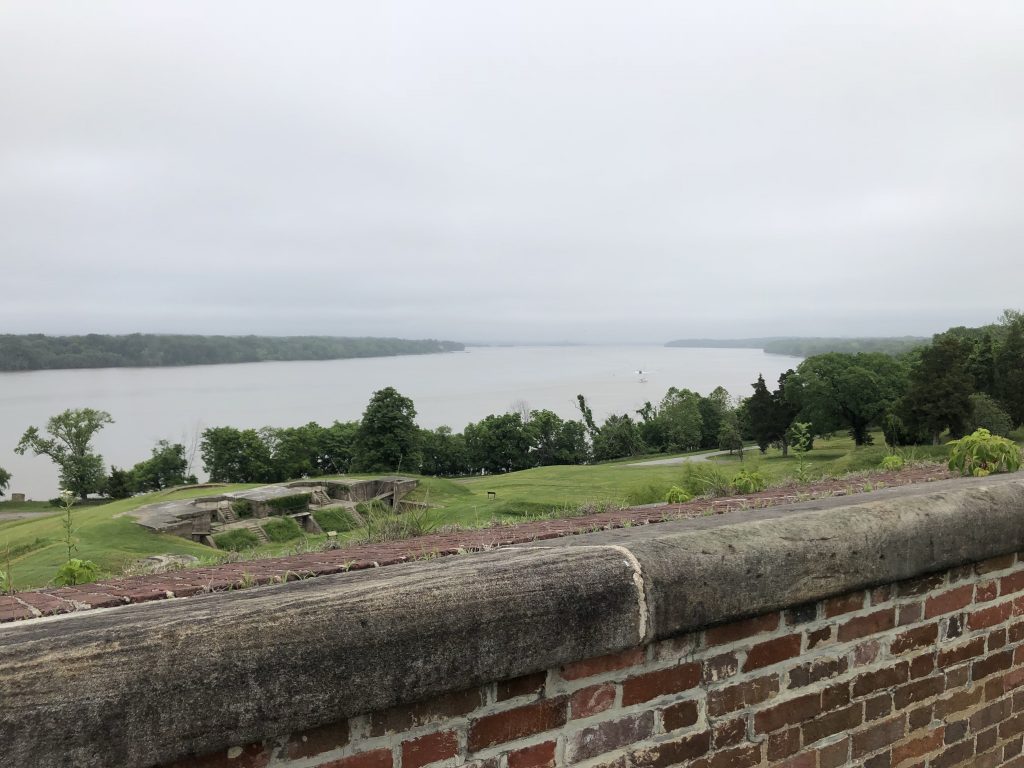

Even before I moved to Delaware, I had my eye on a visit to what I had heard was an excellent mid-19th century, Third System fort that sits on a small island in the middle of the Delaware River, appropriately named Fort Delaware. Back on May 25, 2019, my boys and I made our first trip over to Pea Patch Island to take in the sites of this wonderful old defensive structure. We have since returned a few more times – it’s a really nice experience.

Today, the island and fort are contained within Fort Delaware State Park, and park staff engage in living history presentations on the island as if it was 1864. Most everyone on the island is “in-character” demonstrating various aspects of life in a coastal fortification turned prison during the Civil War.

Since the fort is located on an island, the only access is by ferry boat from Delaware City. It also operates seasonally, shutting down visitor access between October and April. We bought our timed tickets in advance online, but I think it is also possible to get walk-up tickets from the gift shop. After a quick stop at the restroom, we were ready to board the Delafort for the 10-minute ride over to the park.

Once the ferry docks on the island, a tram takes visitors across the marshy part of the island over toward the historical fort. An audio presentation during the ride talks about some of the history of the island, as well as describing some of the wildlife that can be seen in the marsh as you go by. Eventually, as you make the transition to dry land, the massive fort comes into view.

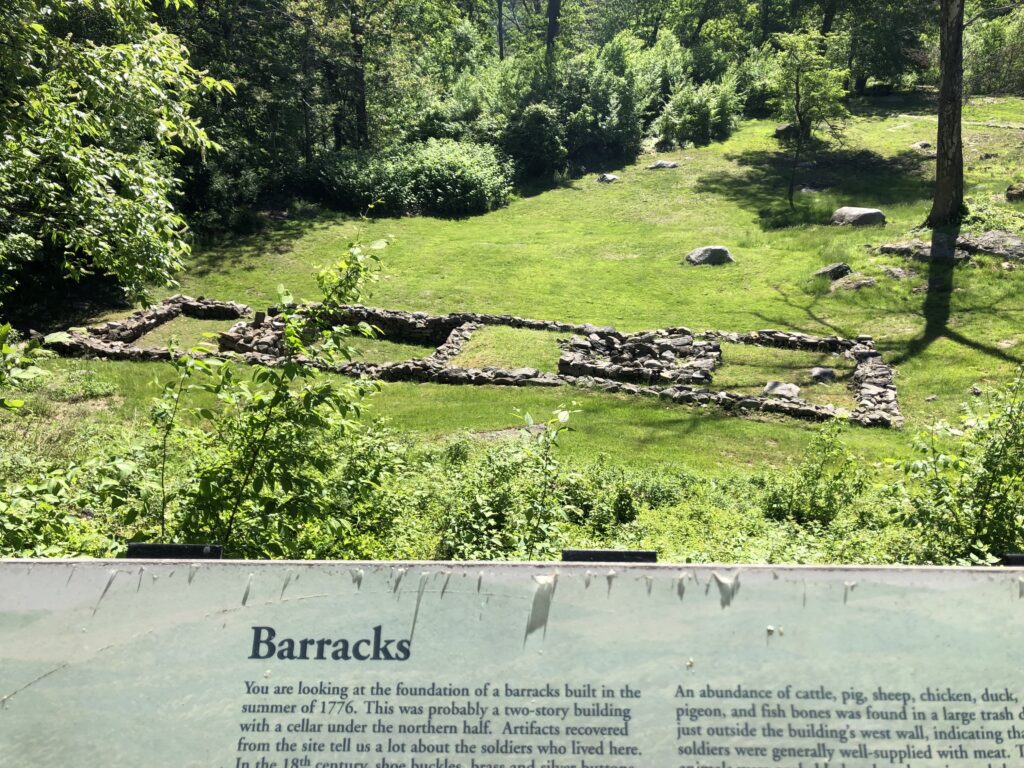

Built with the intention of defending Wilmington and Philadelphia from naval attack, the fort was completed in 1859 – just in time to be garrisoned at the outbreak of the Civil War. Like many of the Third System forts, Fort Delaware went through a series of Endicott conversions in the late 1890s to install larger caliber guns in huge concrete emplacements. The remains of the Endicott batteries can be seen on the south side of the island near the modern restrooms, and immediately to the right as you enter the fort. These days, the concrete structures serve mainly as bat habitats.

Every time we have gone, the interpretation of life at the fort has been wonderful. The staff does an excellent job of making the place feel alive as you tour through the various areas within the fort. Favorites for us have been the laundry, mess hall, and blacksmith shop.

But this was a fort after all, so the real draw is the artillery! Sadly, there isn’t much here in the way of guns, and I believe that what they do have are reproductions. They do a LOT of artillery demonstrations here and it’s generally not safe to do those with weapons that are over 150 years old at this point. A favorite memory for me is from our first visit, when the boys were able to man one of the guns themselves and participate in a firing drill.

As cool as the guns and casemates are, none of the fort’s defenses were ever tested by an enemy in any era. The main Civil War story here is of the island’s use as a prison camp. Thousands of captured Confederates were confined here. Many died, and there were even a few daring escapes that took place. At the height of it, there were dozens of prison barracks built outside of the fort walls for enlisted men. Captured officers were generally kept within the fort itself. The park has rebuilt one of the barracks from a set of original plans to give visitors a feel for what the conditions would have been like, but it doesn’t do justice to the scale of the prison population that was kept here.

As a fort nerd, I really enjoy going to Fort Delaware. Between the ferry ride and the in-character interpretation of the place, each visit is a true experience. And the fort is in terrific shape – so many of the Third System forts have been messed with over the years – with some becoming almost unrecognizable after going through Endicott conversions. Seeing one that is still at its original height and with many of the interior structures still intact is a real treat. I can’t wait to plan my next visit in the spring.