Civil War Artillery: Ammunition

Before we get into more details about the weapons themselves, let’s look at the types of rounds they would have fired, and what they’d have been used for. Understanding these is critical to interpreting official reports from the battles, and getting a sense for what soldiers in the Civil War faced when they were in combat.

There are 5 main types of Civil War ordnance:

Solid-shot

A type of long-range ammunition, this is what people commonly think of as a “cannon ball”. In a smoothbore weapon, this type would be round, and probably called a “ball”; while in a rifled weapon, it would be more conical or “bullet”-shaped, and would normally be referred to as a “bolt”.

As the name implies, this is a solid hunk of metal (usually iron) that is fired out of the cannon. It was used primarily against buildings or soft fortifications, but could also be fired into trees, turning them into deadly flying splinters, or heavy falling logs for anti-personnel purposes. Fired at a low angle against lines of troops in open fields, solid-shot would tend to bounce through the waves of men, taking them out 2 or 3 at a time as it did. This had more of a psychological impact than a physically-destructive one.

In some cases (like during J.E.B. Stuart’s bombardment of Carlisle) these rounds would be placed in a fire or furnace right before being loaded into a cannon so that they would become red hot. In this way, when fired against wooden buildings, the structures would likely catch on fire.

Shell

Another long-range munition, the shell is just that – a hollowed-out ball (for a smoothbore) or “bullet” (for a rifled gun) that contains some form of explosive (in the Civil War, that was gunpowder). The idea was to create a flying bomb that would detonate and spray shrapnel and fire in all directions. This was especially deadly against enemy artillery and munitions.

There were two mechanisms used to detonate the rounds: the newly-invented percussion fuse, or a more traditional timing fuse. These were screwed into the shell at the time of firing, so the cannoneer could select how his fire was going to behave each time.

The percussion fuse was designed to explode on impact. The jolt of the gun being fired armed the round, and then as soon as it struck something – the ground, a building, a tree – it would detonate. Since this was a relatively new technology, and the south didn’t have very good manufacturing facilities, their percussion fuses had a very high failure rate. Many Confederate rounds equipped with this type of fuse failed to detonate.

The timing fuse was used much more commonly. This consisted of a selectable paper fuse that would be ignited by the blast of firing the weapon, and explode after a few seconds. The idea was to time it so the ordnance would explode over top of other cannons, ammunition wagons, or troops so that the shrapnel would rain down on them.

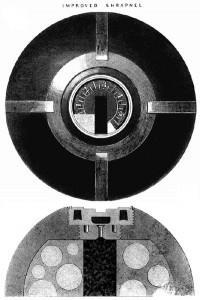

Case-shot

Very similar to shell, this is a hollowed-out round that contained not only gunpowder, but small iron or lead balls, too. This was shell’s anti-personnel cousin. All the same information about fuse types and their purposes that I talked about for shell also applies to case-shot.

This type of munition was very commonly used (and with great effect) during the Civil War, and you’ll see it mentioned in official battle reports from both artillery and infantry commanders frequently. In some of those reports (especially when referencing rounds from smoothbore weapons) this round may be referred to as “spherical case“.

When used with timed fuses, the round could be configured (by cutting the paper fuse extremely short) so that it exploded just before it left the barrel. This method could be used in place of canister in a last resort, low-ammunition situation. Because of the dangers associated with knowingly setting off an explosion that could very easily end up just a few feet in front of your own men, this was not the preferred use.

Canister

This was the really nasty, short-range, anti-personnel stuff. Basically, it’s a large tin can (like an over-sized soup can) filled with saw dust and dozens of lead or iron balls. When fired, the can would shred immediately, creating additional shrapnel. Canister rounds effectively made a cannon into a giant shotgun.

As you can well imagine, this was brutally deadly against the types of line-of-battle formations that were used during the Civil War. It certainly gives you an appreciation for what the men in Pickett’s Charge must have been thinking, knowing that they were walking into this type of ordnance.

Grape-shot

Less commonly-used by the time of the Civil War, this was the precursor to the more effective anti-personnel rounds (like case-shot and canister) that came later. In battle reports, this type may simply be referred to as “grape” – a name that comes from its visual similarity to a bunch of grapes hanging on a vine.

There were several variations of this type of munition, but generally the round consisted of medium-sized iron balls, arranged on plates with a rod holding them together. The whole thing was then placed in a canvas sack. When fired, the round would split apart with the bottom plate pressing forward, sending the balls spreading out through the air toward the enemy.

You can see how the less-bulky and awkward case-shots and canisters would be much better than the heavy, overly-complicated grape-shot. Once troops began using trenches and other breastworks that couldn’t be effectively hit from straight on, case-shot (which could be exploded from above and had a much longer range) became the favored anti-personnel round.

So that’s the general overview of Civil War ordnance types. We’ll start examining how to identify the different models of field pieces used during the war in the next installment of the series.