Civil War Artillery: Iron Guns

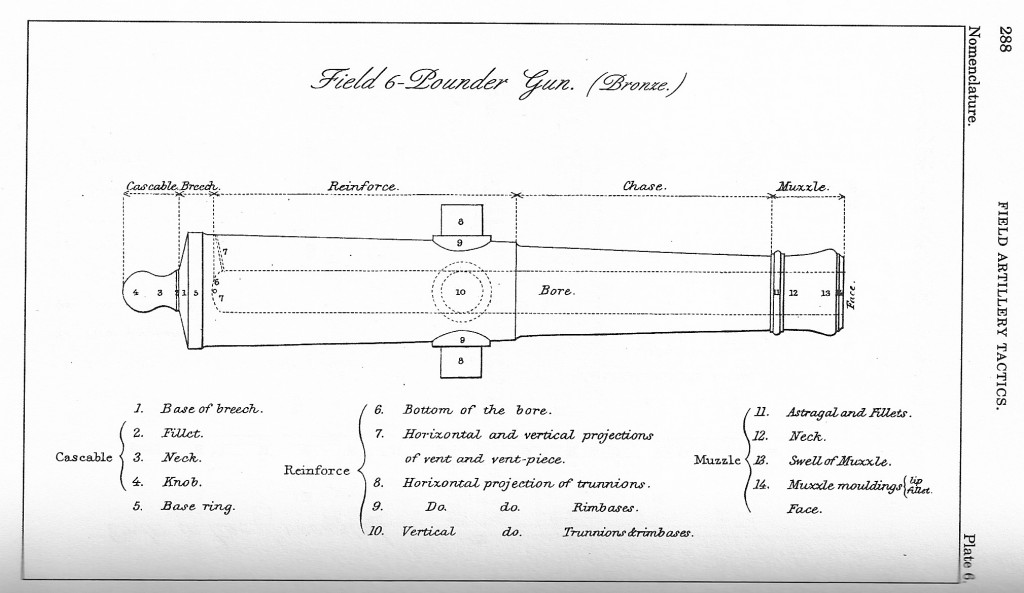

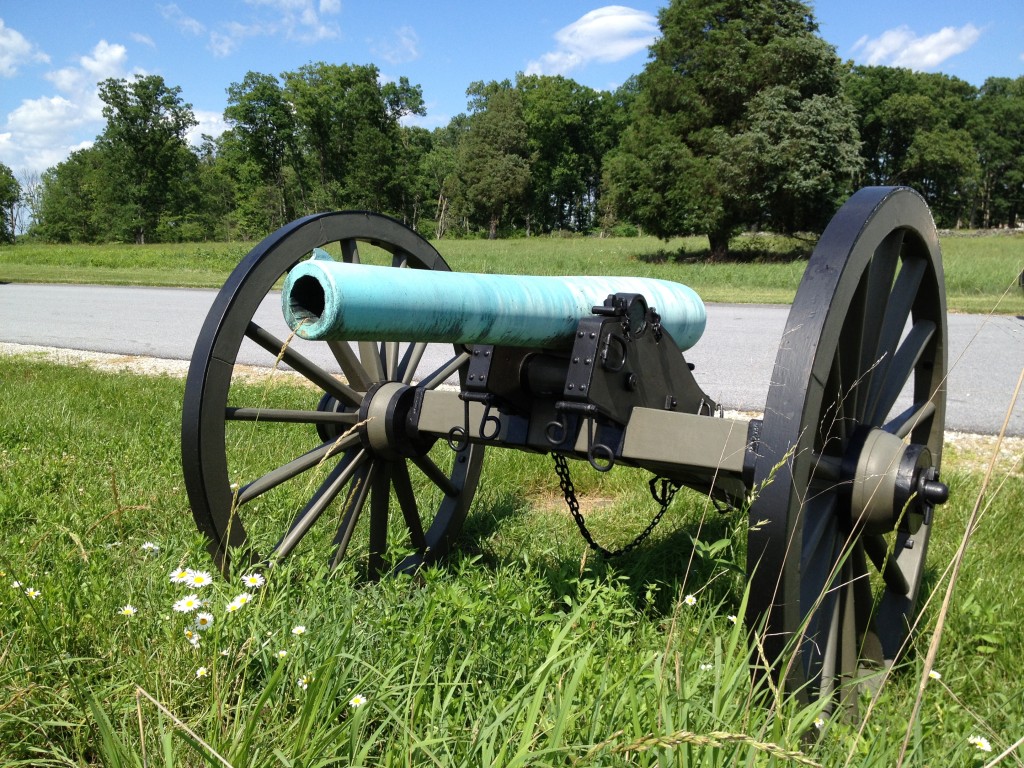

One of the things that I’ve become more interested in over the years is artillery – especially the artillery that was used during the Civil War. I started a series a few months ago to explain some of the basics of these weapons – it is best to see that article first to get familiar with the “anatomy” of the guns. Last time, we looked at some examples of bronze guns from the period. Today, I want to explain how to identify some of the different types of iron cannons, using familiar examples from the collection at Gettysburg.

There are a few main types of iron guns that we’ll be looking at today:

Parrott Rifle

Overview: Designed by Robert Parker Parrott at the West Point Foundry, this weapon was popular in the US arsenal because it was relatively cheap to make. The main part of the gun tube was made from cast iron, and the thicker reinforce around the breech was made from wrought iron. Unfortunately, metalworking technology wasn’t what it is today, and the foundries of the period had trouble fitting the two metals together. Sometimes a gap or bubble would form under the reinforce, and after repeated use, the cannon might burst at that seam. This was more of a perception problem than a real one, but the reputation stuck nonetheless.

Photos:

How to Identify: Look for black guns with a thick band around the reinforce. They’re very unique-looking. Actual pieces will have markings on the muzzle, and an “R.P.P” (for Robert Parker Parrott) and “W.P.F” (for West Point Foundry) on the end of the trunnions. There are both 10-pounder and 20-pounder versions at Gettysburg, with the 20-pounders (like the one pictured above) obviously being somewhat larger. Some of the earlier 10-pounders have a slight muzzle flare. There are plenty of fake Parrotts on the field, too.

Exceptions: Not all the guns of this design were made at the West Point Foundry. There were Confederate copies made at Tredegar and other facilities, and once you’ve seen one, you can tell that they are definitely of a lesser quality. There are a couple Confederate “Parrotts” on the field at Gettysburg right below the Longstreet Tower.

Fakes: As I said above, there are plenty of fakes when it comes to Parrotts. These can be hard to spot from a distance, though. Of course, any gun without any discernible markings on the muzzle, trunnions, or breech is suspect. The best long-distance indication that I’ve found is a horizontal casting seam running the length of the gun. Real cannons aren’t cast in halves like this:

I also noticed on this particular example that the muzzle swell is quite severe. It’s got a short length and a wide diameter. Real Parrott muzzle swells are more gradual.

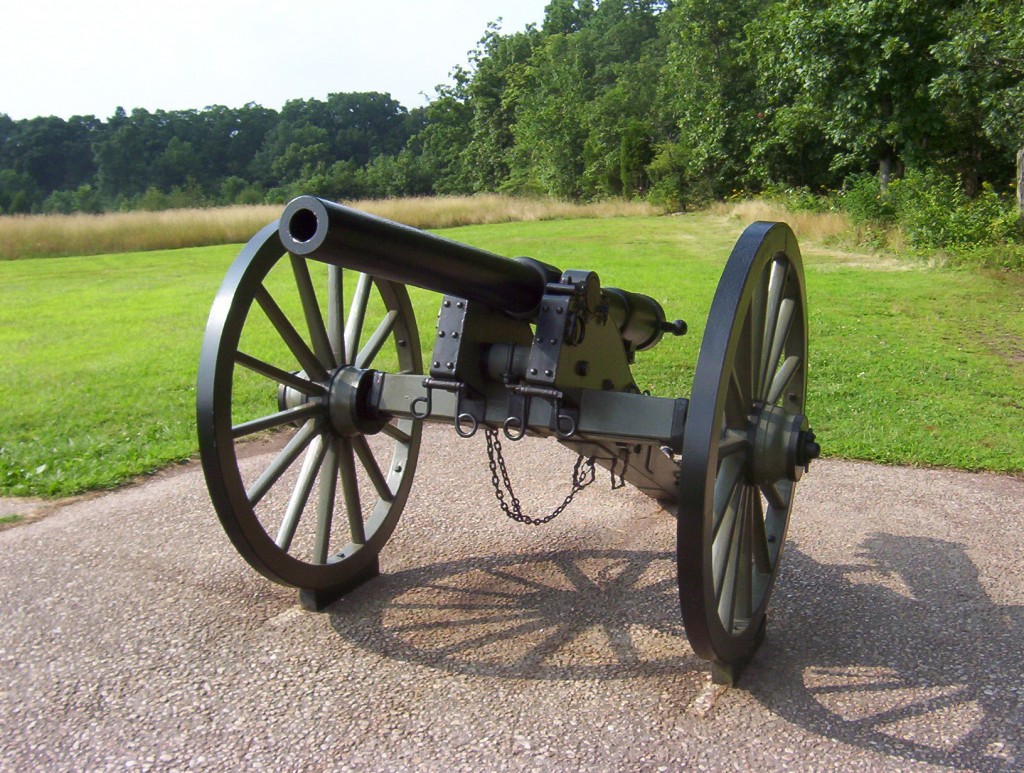

Model 1861 3-inch Ordnance Rifle

Overview: An advanced weapon for the time, this was a very strong and light gun made entirely from wrought iron. These technologically-advanced weapons were made by “P.I.Co.” or the Phoenix Iron Company, headquarted just northwest of Valley Forge, PA.

Photos:

How to Identify: Being iron weapons, the guns on display are all painted black. The 3-inch Ordnance Rifle has a very sleek shape, with a smooth taper going from breech to muzzle. This is the same shape we talked about for the 14-pounder James Rifle in the previous post. It’s obviously pretty easy to tell the difference between this and the Parrott, as there’s no reinforcing band.

Exceptions: Every 3-inch Ordnance Rifle I’ve seen is the same design. Gettysburg does have at least 1 that was made in 1866, so we know for a fact that it was never actually used in battle. There were Confederate copies, too, but I don’t think that Gettysburg has any out on the field.

Fakes: Just like the fake Parrotts, fake 3-inch Ordnance Rifles lack muzzle, trunnion, and breech markings and will also have a casting seam running the length of the barrel. Spotting them from a distance is even easier though, as they have a totally different, much pointier shape at the back. Just look at this cascable and compare it to the real one above (also – see the casting seam?):

Whitworth Rifle

Overview: My favorite guns on the field at Gettysburg, these are totally unique British-made weapons. The Confederates had 2 of these at the Battle of Gettysburg, and there are 2 on the field today (though probably not the actual ones that were used in 1863) placed near where they were for the battle – on Oak Hill right behind the Eternal Light Peace Memorial.

The Whitworth design was so advanced, it was actually ahead of its time. The most obvious thing about it is that it’s a breechloader like modern cannons. The gun had a maximum range of almost 6 miles, but this wasn’t as useful as it sounds. In an age when you’re only going to fire at what you can see, any range more than a mile is pretty much wasted. In the case of the Whitworth, the extra range was used for counter-battery work – these were used to pick off enemy cannons outside of the enemy’s range, and they were deadly accurate when used like this.

All of this technology wasn’t without problems of course: the breech didn’t seal properly all the time causing gases to leak out, weakening the force of the explosion. The hinge that opened the breech would seize up frequently if not properly maintained, forcing the gun to be used as a muzzleloader instead. The barrel wasn’t rifled in the traditional sense, but was instead a very severely twisted hexagonal tube. This required very specialized ammunition, which was another problem – especially for the blockaded and agrarian Confederacy. That severe twist also exerted so much torque when the weapon was fired, that the wooden wheels frequently broke off of the gun carriages.

Photos:

How to Identify: A very cylindrical weapon, the initial indicator on these is the ring around the barrel at the trunnions. Viewed from the rear, the obvious feature is the opening breech. There are two knobs on the breech for cranking the back open, and a giant hinge on the right side.

Exceptions: I’ve only ever seen the 2 that are at Gettysburg. So far as I know, they all share the same design. One of the ones that Gettysburg has does have a field modification, though. There is a guard on the back of the breech to keep the friction primer from popping out when the weapon was fired. That was not part of the original design.

Fakes: I’ve never encountered any fake Whitworths, though I’ve seen people build their own re-creations of the weapon from old plans.