Battlefield Visits: Road Trip to Chattanooga, Part 3: On to Atlanta!

From my travels, May 28, 2019.

This was going to be an exciting day. My nephew and I were going to check a lot of battlefields off the list. We got up early (no small task for a teenager) and got on the road before 9:30am.

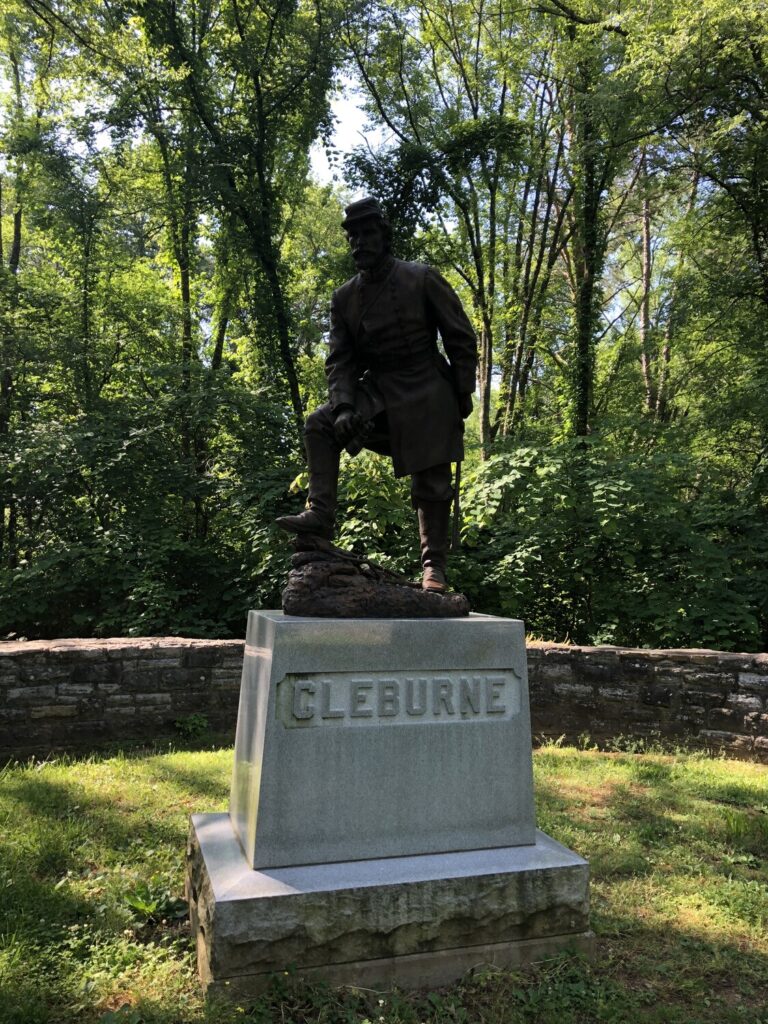

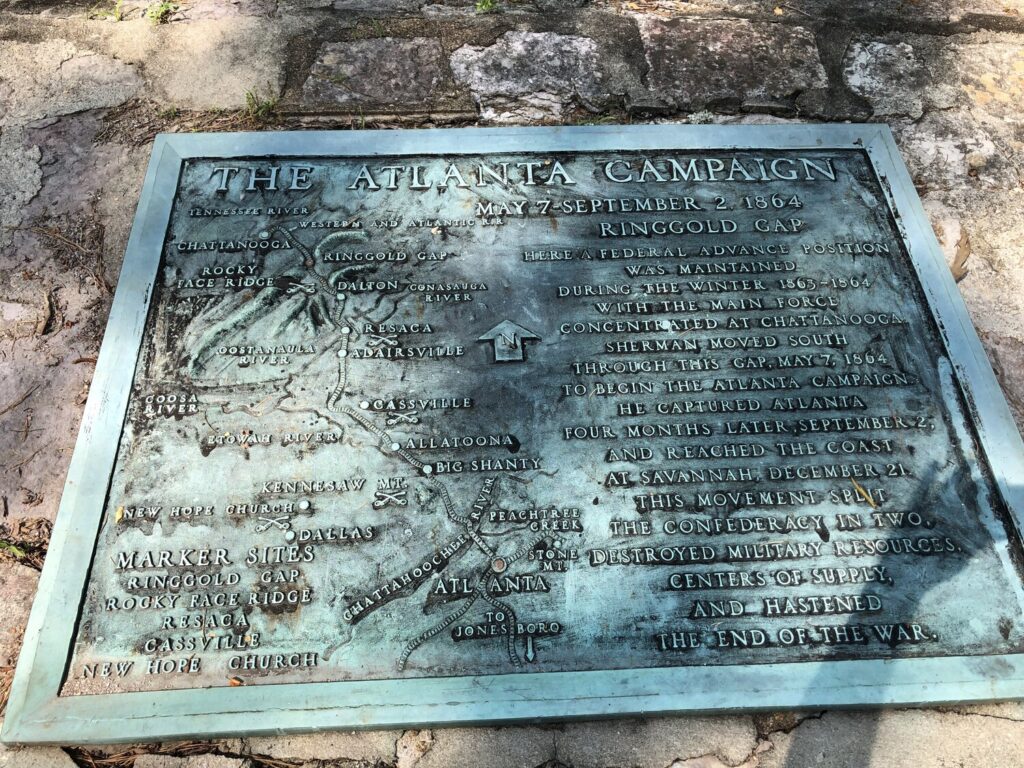

Battle of Ringgold Gap – Civil War Battlefield #109

Not too far down the road, we came to our first stop, the Battle of Ringgold Gap. While not considered part of the Atlanta Campaign, this was right along our route, and I’d never visited before.

The story here is that Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s men fought for over 5 hours as a rear guard after the Confederate army was forced off of Missionary Ridge outside of Chattanooga. The Union attack here was not well executed, and Grant made the call not to pursue beyond the gap, returning his troops to the defenses of Chattanooga.

We checked out another of the New York monuments – very much like the one at Wauhatchie the day before. It was a little off the beaten path, so that was pretty cool. The main visitor focus for this battlefield is on the small “pocket park” that was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps back during the Great Depression. It’s a parking area with a few markers and picnic tables right off of US-41.

The gap itself has clearly been widened over the years to make room for I-75, but you can see that even in its natural state it would have been quite substantial in late 1863.

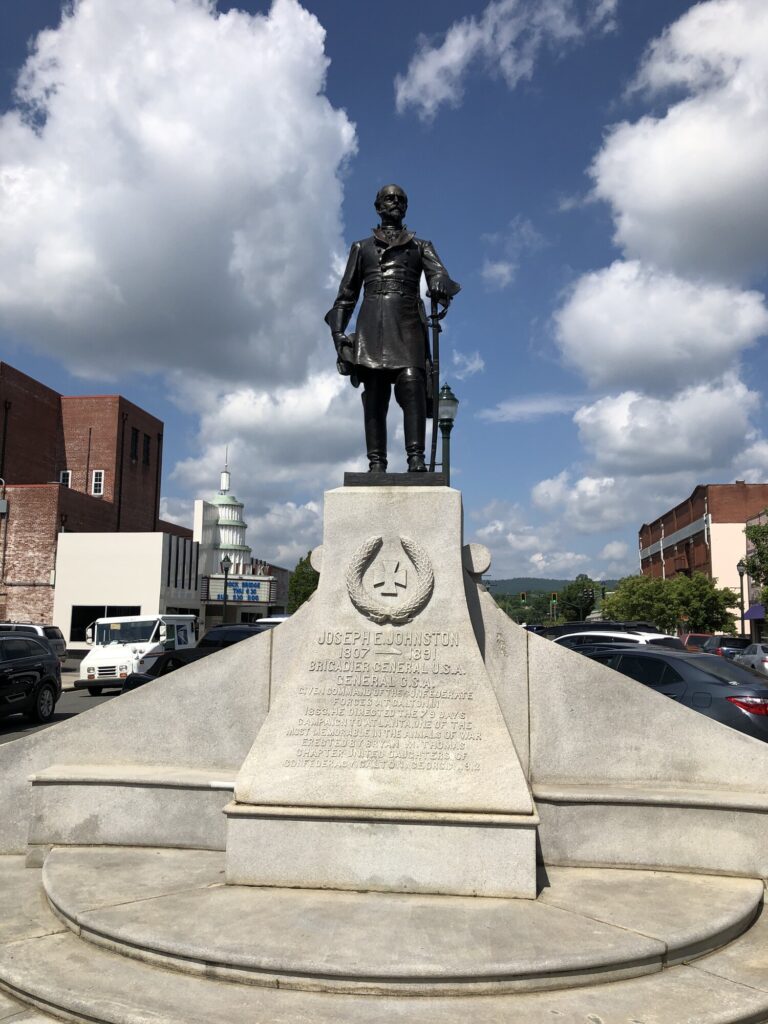

First Battle of Dalton – Civil War Battlefield #110

Fighting at the First Battle of Dalton took place in Mill Creek Gap. This is another location that is marked by a CCC “pocket park” just in front of the Georgia State Patrol Station on US-41.

There’s a trail near the parking area that leads a little farther up the ridge to the site of Fort Fisk – perhaps named for some distant relative of his? The surprise of seeing that sign definitely put a smile on his face. A nice memory to be sure.

Second Battle of Dalton – Civil War Battlefield #111

The field of the Second Battle of Dalton seems to have been obliterated by modern development. I had a hard time finding any markers for it, and even a couple of the visitors centers and museums in town were unable to direct me to anything concrete.

That said, my nephew and I got to spend a little time driving around the town, and it seems like a pretty nice place.

Battle of Rocky Face Ridge – Civil War Battlefield #112

I know that a park has since been established north of Dalton to help preserve some of the history of the Battle of Rocky Face Ridge, but that did not exist at the time of my visit. My nephew and I took a look at the southern portion of the field, in Dug Gap.

There is a small parking area there and a few markers and waysides to give the visitor a little bit of the story. From there, we walked on a short trail up to the ridge and saw some of the rock formations and cliffs. It was a very peaceful spot.

Battle of Resaca – Civil War Battlefield #113

We hit the first of our disappointments for the day at the next stop: the Battle of Resaca. There is a nice park here preserving part of the Union section of the battlefield, but it is only open Friday – Sunday. Of course, we were visiting on a Tuesday.

We were able to park just outside the gate, and see a couple of markers that were nearby, but neither of us wanted to press our luck exploring any farther. One thing that I really liked was the reproduction chevaux de frise that stand right next to the gate. At least there won’t be any cavalry attacks here!

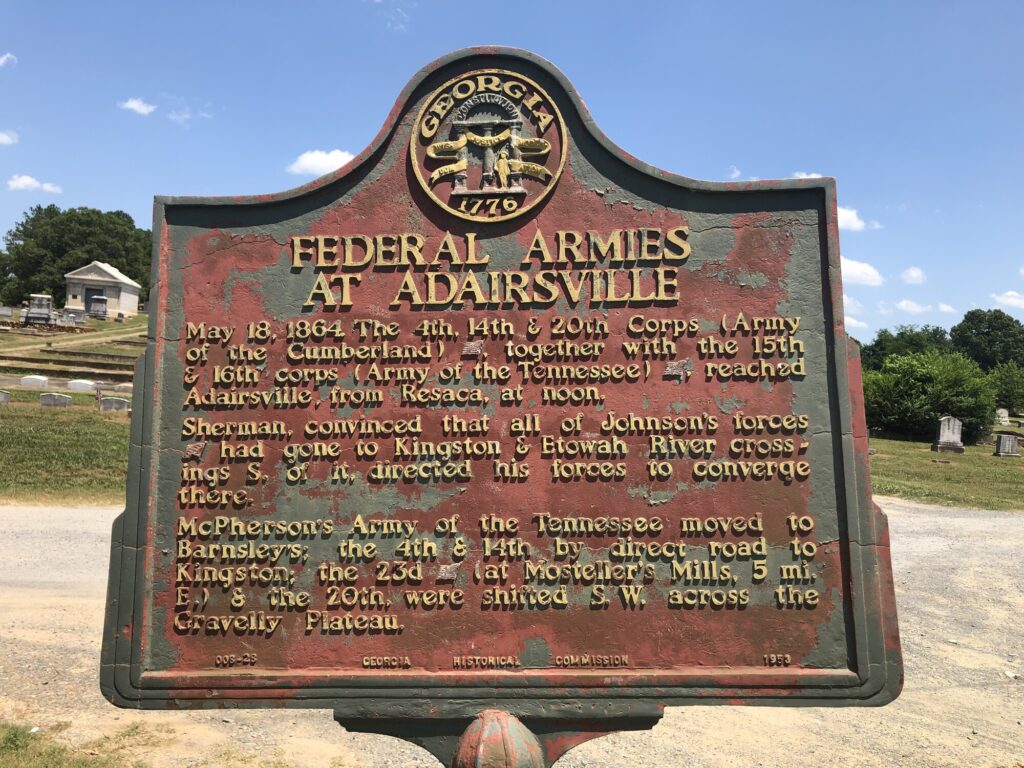

Battle of Adairsville – Civil War Battlefield #114

There isn’t much going on at the site of the Battle of Adairsville. In truth – none of the battles of this campaign produced the kind of fighting and casualties that one would expect from major Civil War battles. This campaign was really a master class in maneuver given by Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman.

We were able to find a few, kind of rough-looking, roadside markers near a cemetery in town, but that was about it.

Battle of Allatoona – Civil War Battlefield #115

There have been a lot of changes to the field of the Battle of Allatoona since 1864. The most obvious one hits you as soon as you park your car and see the huge earthen dam that holds back the artificially-created Lake Allatoona. That means that a part of this field is now underwater. The day we were there featured plenty of activity going on, with people walking along the trails and taking out their boats.

Like so many of the battlefields we are seeing on this trip, the reason it came to be was all about the railroad. The Western and Atlantic Railroad cut right through a gap here, and that narrow channel through the mountain still exists. The railroad has been converted to a walking path, and about half way down the trail, there is a set of stairs leading up the side to the star fort which commanded the approaches here.

Apart from the remains of the fort, there are several waysides and even a few monuments – the coolest of which are stone markers that commemorate the different States that supplied men for this fight. I couldn’t resist having my nephew pose with the North Carolina one, since that is where he grew up. Sadly, there was no Maryland monument.

Battle of New Hope Church – Civil War Battlefield #116

The church from the Battle of New Hope Church still exists, and while there is another of the “pocket parks” here, I get the sense that the congregation takes a certain amount of pride in the field. There are worm fences and even some earthworks here, and they were in pretty good shape.

As we get closer to Atlanta, less and less land is preserved in the sprawl of the modern metropolis. Only small little landmarks are left in the wake of countless new neighborhoods. That’s the story here as well.

Battle of Dallas – Civil War Battlefield #117

I’ll be honest – I was very confused by the Battle of Dallas. And it isn’t like this is my first time on a battlefield. There are plenty of markers scattered around town, but the places that they seem to label as being part of the defensive lines don’t seem all that defensible to me. Maybe the terrain has changed in the last 150+ years with the massive growth of Atlanta?

This feels like the kind of place that I would need to study a lot, and come back with some period maps to try to get my head around it. I just wasn’t able to grasp it on the field.

I will add: the best wayside that I found was over behind the Chamber of Commerce building.

Battle of Pickett’s Mill – Civil War Battlefield #118

The Battle of Pickett’s Mill has been partially preserved as a Georgia State Park, but like Resaca, it wasn’t open on the day I can through. It’s a shame, because it seems like it may be pretty solidly interpreted. For now, my nephew and I had to settle for the marker in the small parking spot out front.

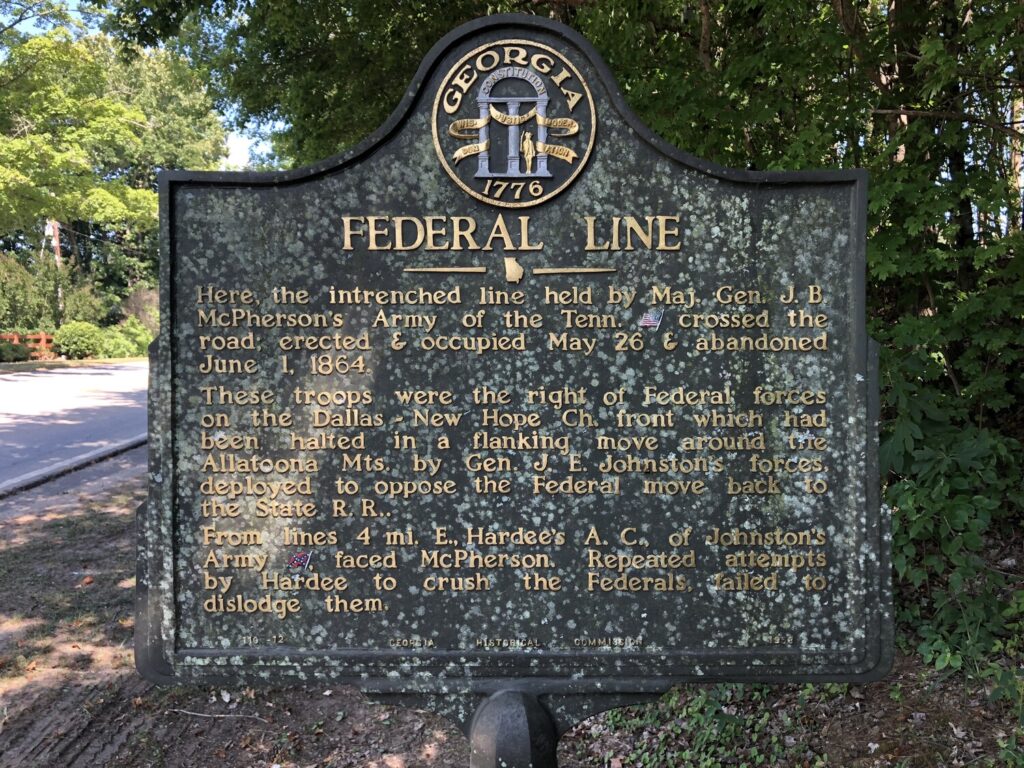

Battle of Marietta – Civil War Battlefield #119

I was initially confused by the Battle of Marietta. It turns out that this was really a series of smaller actions that occurred around the area rather than one concerted fight. We visited the site of Gilgal Church, which had some cool reconstructed earthworks.

11 battlefields was a fine number for one day. As it was starting to get late, we decided to head back to Chattanooga and resume closer to Atlanta in the morning. There would be a few surprises coming for us – mostly pleasant ones.