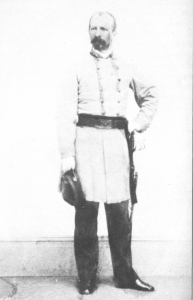

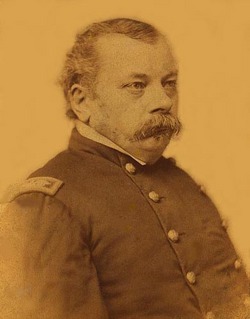

Joseph Sudsburg

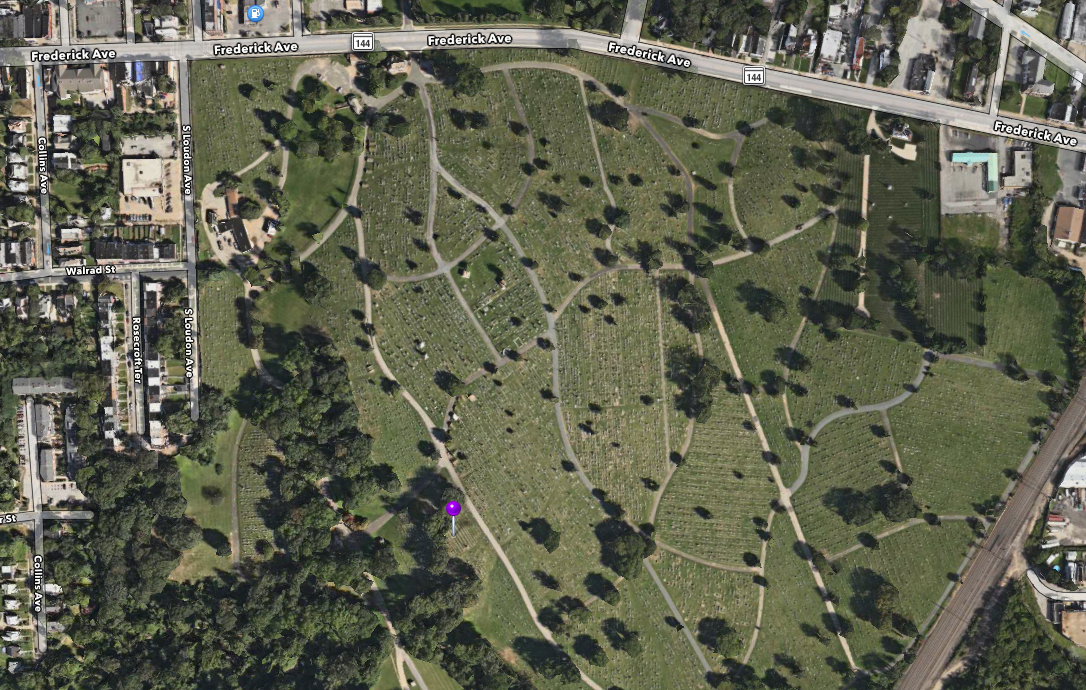

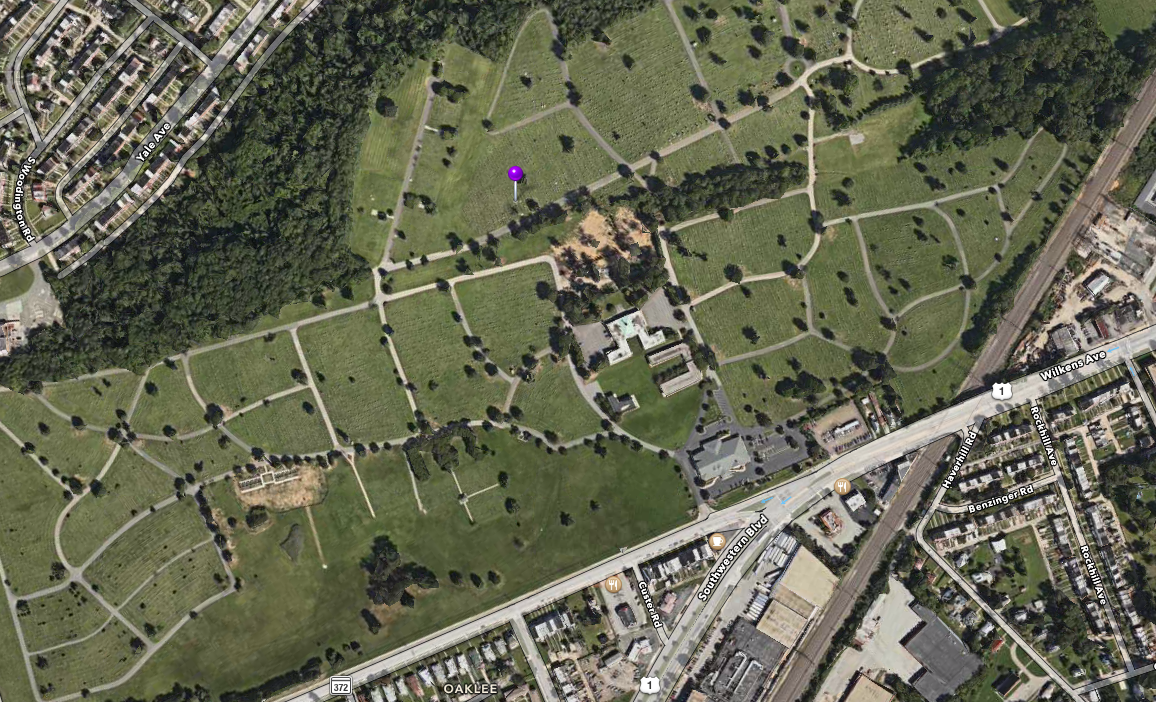

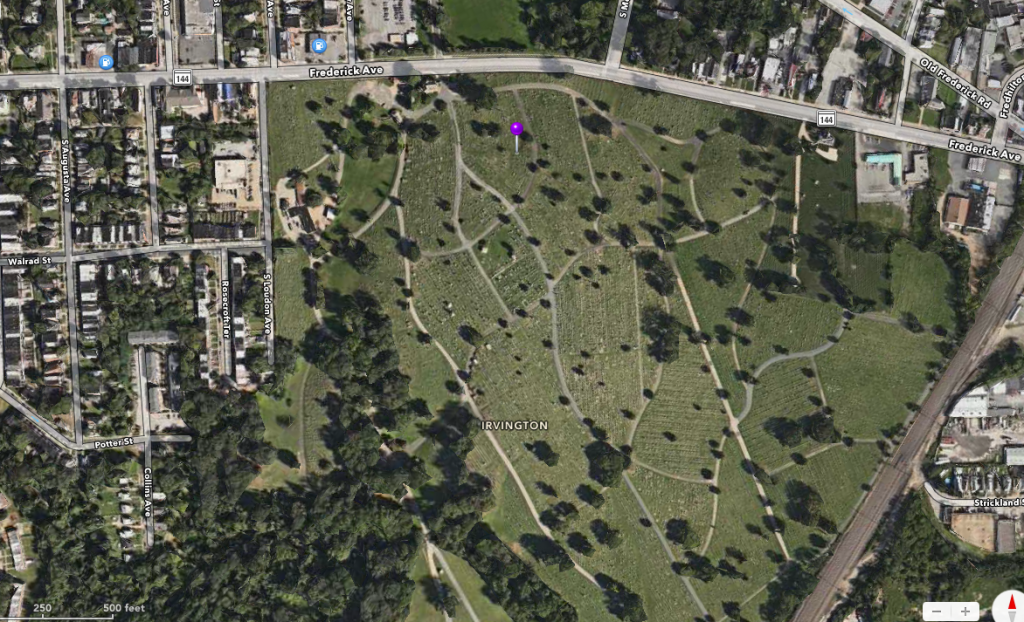

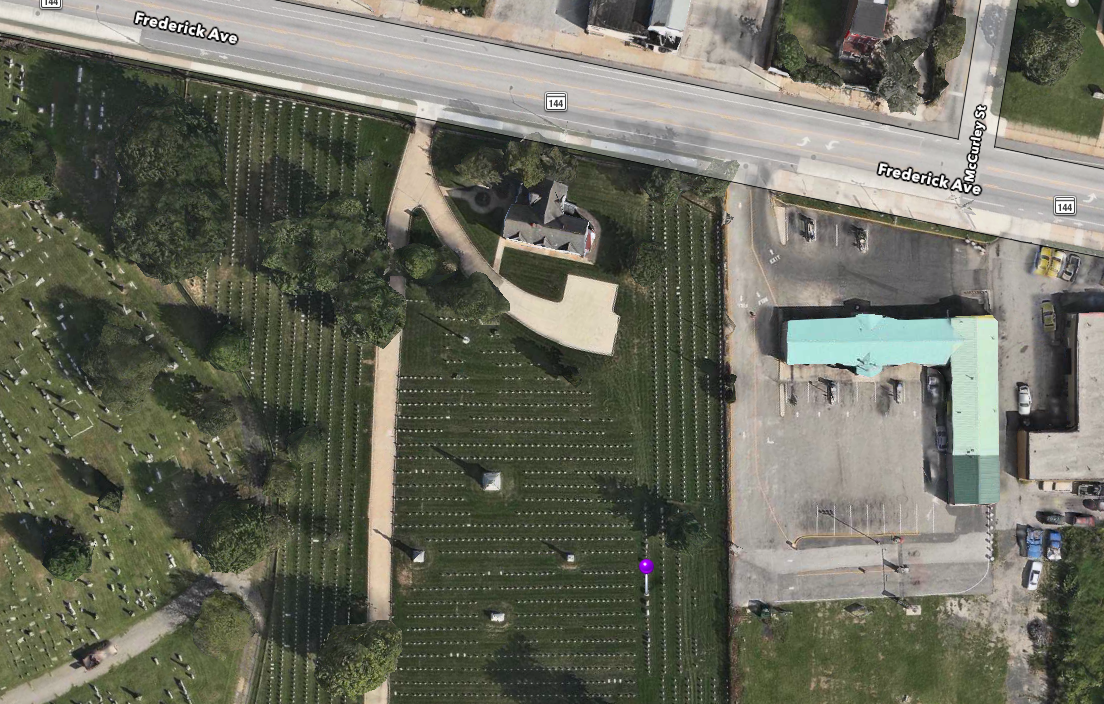

I want to make sure that I’m clear on this: we’re leaving Loudon Park Cemetery temporarily and going next door to Loudon Park National Cemetery to find another veteran of the Battle of Gettysburg – and a Union man this time: Col. Joseph M. Sudsburg.

A Bavarian by birth, Col. Sudsburg had emigrated to America after taking part in the failed revolution in Poland in 1846. He ended up settling in Baltimore, and his previous military experience (even though he was on the losing side) led to a Colonel’s commission and the command of the 3rd MD Infantry when the Civil War broke out. His leadership of the unit also helped to attract many other European immigrants to service in the 3rd MD.

At Gettysburg, he was still in command of the 3rd MD, attached to McDougall’s brigade of the 12th Corps. The unit participated in the combat at Culp’s Hill on the morning of July 3, but spent most of that day in a reserve position. Their casualty figures tell the story pretty well: of the 290 men present for duty, they lost only 8 – and only 1 of those was a fatality.

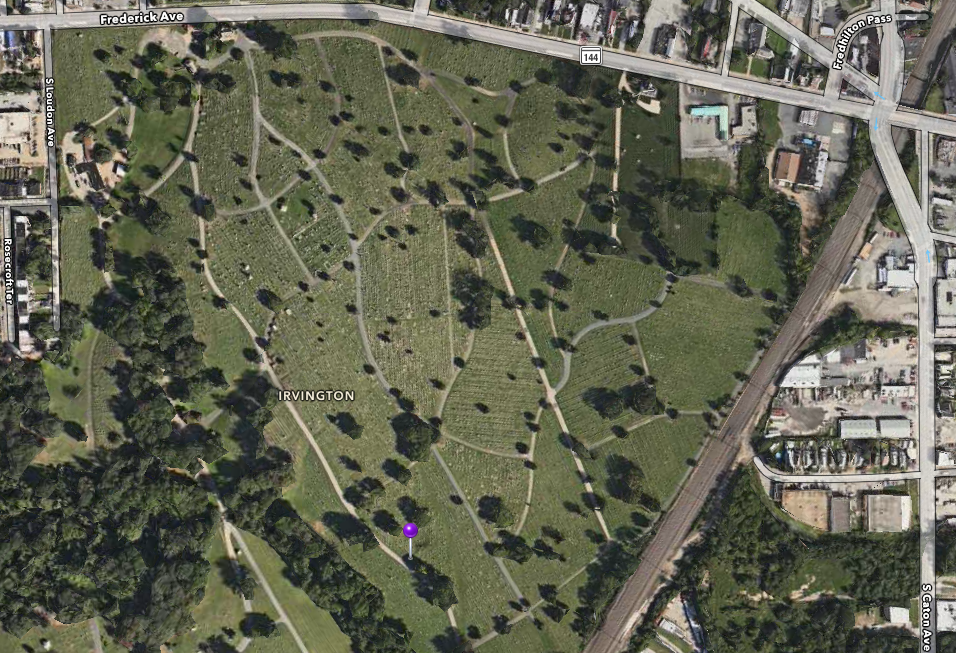

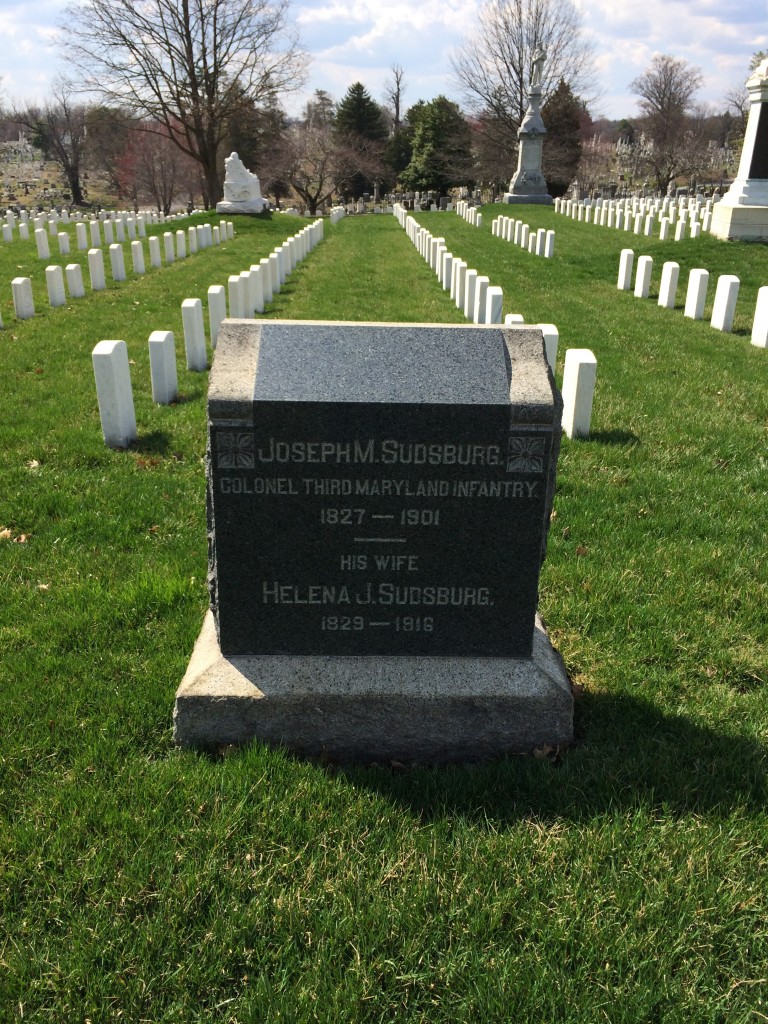

Col. Sudsburg’s monument is located in the Officer’s section, near the eastern fence in Loudon Park National Cemetery:

In the next installment, we’ll see the grave of a Union artillerist who was present at Gettysburg.