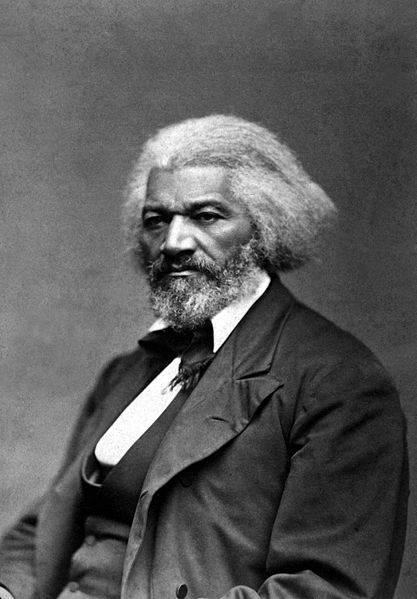

Happy Birthday, Frederick Douglass!

Today marks the adopted birthday of one of my heroes, Frederick Douglass.

Since he was born as a slave, he had no way of knowing when his birthday fell exactly, but he thought Valentine’s Day was as good a day as any to pick for the celebration. We also don’t know for certain what year he was born, but it was probably around 1818. His birth site is pretty clear from his own writings (though the Maryland State Roads Commission doesn’t seem to have gotten the memo).

Whatever the truth is, we can still take a day each year to remember what a great man he was. Happy 196th, Mr. Douglass!

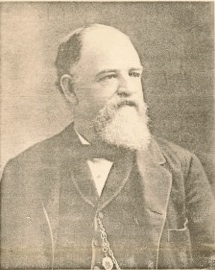

George R. “Cracker-baker” Skillman

This is a very long post about a piece of Skillman family history. There’s plenty of general interest history in here as well, but I go very deep in the weeds in some places. If you’ve stumbled onto this post via a web search and think that we may be related, please drop me a line!

When I recently wrote about my family’s connection to the Great Baltimore Fire, it got my curiosity going again about my great-great-great-grandfather, George R. Skillman. Since there are so many men named “George R. Skillman” in our family, we’ve always called him “Cracker-baker George”.

For a long time, that was pretty much all we knew about him: he lived in Baltimore, had some type of association with the Maryland Institute, and made a name for himself in cracker-baking. That was it.

In recent years, I’ve done some digging on Ancestry, and was able to locate some Census records and his Civil War draft registration on there, but my mission at the time was to try to get information on the whole family, not to just drill down on one or two members, so I never got that deep on his life story. That all changed with the anniversary of the Great Baltimore Fire. I wanted to find out more about who this guy was.

I collected all the data that I had from the traditional family story, to the Census records I found online, and went down to the main Enoch Pratt library, hoping that they would have some good sources. I’m happy to report that they were tremendously helpful. I was able to find some information about companies he worked for, and even some clues about a few other relatives in Pratt’s collection of books. Searching the city directories and the online archives of The Baltimore Sun (which the library subscribes to) were instrumental in putting some of the pieces together.

There are still plenty of holes – one of the Pratt librarians told me that this is probably always going to look like Swiss cheese – but here’s the story of his life that I have (so far):

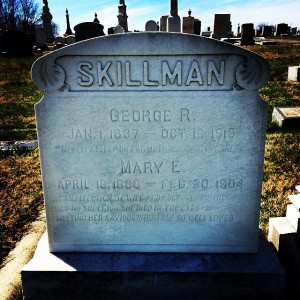

George R. Skillman was born January 1, 1837 in Baltimore. His parents were F. Robert J. Skillman and Naomi Sophia (Miller) Skillman.

He was a member of the Methodist Episcopal Church. His family attended services at High Street Methodist Episcopal (originally built at 230 S. High St. – now a parking lot) and later in life, at Grace Methodist Episcopal in Baltimore.

The first reference to him that I found was in The Sun on March 8, 1858. He apparently attended a meeting in Temperance Hall in Baltimore, where the attendees were discussing their support for “The President’s Plan” regarding Kansas. This is a reference to the Lecompton Plan for Kansas’ state constitution – a constitution that would have allowed slavery in the Sunflower State. From what I’ve been able to find, George was a life-long Democrat, so it isn’t surprising that he’d be supporting President Buchanan as a young man.

On April 22, 1858 he married Mary Elizabeth Pierce. The couple would go on to have 8 children, but three of them wouldn’t survive past their twenties. My particular branch of the family is descended from his 4th son, Robert G. Skillman.

He registered for the draft in 1863, listing his occupation at the time as “Clerk”. The 1864 Woods’ City Directory has him living at 90 N. Eden Street (a house that no longer exists), and shows that he’s working as a “Bookkeeper”, but on January 1, 1864, James Beatty announced in The Sun that he was entering into a copartnership with his clerk, George R. Skillman.

His name is called in the draft June 23, 1864, but he doesn’t end up going to war. By June 28, he’d found a substitute to serve in his place. You could do that back in those days, especially if you were a partner in a prominent manufacturing business.

The same city directory in 1865-1866 shows the first reference to the company that he made his name working for: James Beatty & Co. Steam Cracker, Cake, and Ship Biscuit Bakers. This firm seems to have been one of the largest commercial / industrial baking operations in Baltimore at the time. James’ grandfather was also named James Beatty (what is it with all these people having the same names?), and was the U.S. Government Naval Agent in Baltimore during the War of 1812. The Beatty’s were a prominent (and rich) family in 19th century Baltimore. Civil War nerds like me will also appreciate that “ship biscuit” is the naval term for hardtack, and from records I’ve found, the company was definitely a hardtack supplier for the Union army. The company’s address is listed as “Nos. 92, 94 & 96 Dugan’s Wharf, near Pratt Street” – what is now known as Pier 4 at the Inner Harbor.

In the 1870 Census, George lists his occupation as “Baker”, and on April 4, 1871, he’s granted U.S. Patent 113,356 for his Cracker Machine. Clearly, he was an innovative force in the industry. In an 1873 advertisement for the James Beatty Co., George is still listed as being James’ partner in the business. My feeling is that George became the brains, or the heart of the operation, and that James was providing the capital and the business side.

Sometime before 1878, George moves the family to a nicer house at what is initially listed as “329 Myrtle Ave.”, but later listings all show the property more accurately as being at 1408 Myrtle Ave (the current house at this address was built in 1920).

George joins the Board of Managers for the Maryland Institute in 1878. He would end up serving on the board for the rest of his life. Of course, it was through this association that my family first learned of him. In his first year as a board member, the institute held an exhibition (in those days, the school had a mechanical, vo-tech element to it as well as being an art school) in which the very latest technology was demonstrated. That year, the arc light, and the telephone were the big showpieces. The Baltimore Sun, describing the event 20 years later, had this to say:

On top of the tower of the building was placed one of these lights, with a reflector – a crude forerunner of the now well-known electric searchlight. An incident of this application was that when the light was thrown towards the home of Mr. George R. Skillman, on Myrtle Ave., and Mr. Skillman using the other unique exhibit, the telephone, read by it a newspaper extract to an auditor at the other end of the line.

Alexander Graham Bell had his successful test with the telephone just 2 years before. George was certainly a man who wanted to be on the cutting edge of technology.

His association with the Maryland Institute didn’t stop at serving on the board, though. An advertisement in The Sun on February 23, 1880 announces that “George R. Skillman, esq.” will be giving a lecture that evening about “Saalbec, Athens, and Pompeii”. So he’s a history buff, too.

In 1886, a book called “Half Century’s Progress of the City of Baltimore” was published. It included a one-page profile of James Beatty & Co., that mentioned how James took over the company from his father in 1858 and “some years later” added George R. Skillman as a partner. The article goes on to say that George “retired” from the firm in 1884. This isn’t entirely accurate, it seems. An announcement in The Sun on January 1, 1885 states that the partnership had been dissolved, and that James was bringing his son onboard in George’s place. It goes on to say that George had purchased another piece of property on Greene St., and would be starting his own bakery there.

On December 22, 1885, The Baltimore Sentinel published an article stating that:

Sunday afternoon, a fire destroyed the three upper floors of George R. Skillman’s cracker bakery, in Baltimore. The damage to the building is estimated at $10,000 and to stock and machinery $10-15,000.

Some “retirement”, huh?

The 1886 Woods’ City Directory lists “Skillman, George R.” under the category “Steam Bakers”, with an address at 51-57 N. Greene St. This was the location that was destroyed by the aforementioned fire. Luckily, George was fully-insured, and he rebuilt the business at a location up the street. By 1887, that new listing has appeared as “George R. Skillman Universal Steam Bakery” at 203-211 N. Greene St. (now a parking lot for the nearby University of Maryland campus).

The Sun has several text ads for the company from this period:

That last one is terrific. I have to wonder how much time was wasted by 19th century Baltimoreans in “scolding their cooks” about the low-quality bread they made. There’s also a collection of smaller ads. These are all great:

I think it’s interesting that his early ads are all about bread. In those days, most people baked their own bread at home. Even as late as 1910, only about 30% of bread was store-bought. His marketing push is based around his bread being an affordable luxury. He can make it better than you can yourself, and you might even save time and money. Rather than relying totally on local grocers carrying his bread, he also opens a full-service retail store at the bakery sometime in the 1890s.

On January 1, 1892, an advertisement in The Sun announces that my great-great-grandfather, Robert G. Skillman, has been made a partner in his father’s business. Only 26 years-old at the time, he is the eldest surviving son.

At the same time, George continues improving on the state of the art in his industry. In 1892, he’s granted U.S. Patent 487,431 for a commercial oven he’s invented.

It’s around this time though, that things look like they start going downhill a bit.

On January 27, 1891, The Sun mentions a court case, Edward A.F. Mears v. George R. Skillman. I don’t have any of the details of the case, but I know that George lost, and had to pay a sum of $45 to Mr. Mears.

Another article, entitled “Business Troubles” appears in The Sun on May 7, 1895. Guess what this is about:

George R. Skillman & Co., proprietors of the bakery at 203-211 N. Greene Street and of the restaurant at 225 N. Eutaw Street, made an assignment for the benefit of creditors yesterday to George D. Iverson, trustee. The bond was for $15,000, double the estimated value of the assets, which are said to consist mainly of special machinery. The liabilities, it is said, will aggregate about $30,000….They said the assignment was due to the low price of crackers and cakes, and to depression in the business.

So by 1895, he’s up to his eyeballs in debt, and he can’t seem to find a way out. This sounds like really bad news, except that another announcement appears in The Sun on June 21, 1895 – less than 2 months later:

George D. Iverson, Trustee of George R. Skillman & Co., bakers, under deed of trust for the benefit of creditors, yesterday reconveyed the trust property to the firm, who have settled with all their creditors. George R. & Robert G. Skillman are the members of the firm.

So it looks like George has found a way to pay-off all the people he owed money to. He must have come into some quick cash….

Fast forward to December 4, 1895 when The Sun ran an ad announcing that the Skillman Universal Steam Bakery had been purchased by the New York Biscuit Co. The ad expressed the hope that their customers would continue to support the business. George R. Skillman is listed at the bottom as the “Manager”.

In 1898, the New York Biscuit Co. (now owners of the Skillman Bakery) merged with the American Biscuit and Manufacturing Co., creating the National Biscuit Co. in the process. This conglomerate would later shorten its name to Nabisco. By 1900, they’ve consolidated their operations in Baltimore to the 203-211 N Greene St. location, and George R. Skillman is still the Manager.

But there’s still more trouble brewing.

The Sun publishes an article on July 25, 1899 entitled “To Fight the Trusts – Wholesale Grocers Declare War on Big Corporations”. In the article, its reported that the local grocers don’t want to deal with the larger suppliers, and several have agreed to only buy from smaller, local providers. One of the companies that is specifically targeted in this protest is the National Biscuit Co. that George sold-out to, and is now managing the Baltimore operations of. But there’s about to be another plot twist.

The Polk’s City Directory for 1901 lists the following under “Bakery, Wholesale”:

- Skillman Bakery (National Biscuit Co.), 203-211 N. Greene St., Elmore B. Jeffery, Manager.

- Skillman, George R. (Union Biscuit Co.), 115 S. Frederick St.

By 1903, the listings look like this:

Under “Bakery, Wholesale”:

- National Biscuit Co., 203-211 N. Greene St.

Under “Bakery”:

- Skillman Bread & Pie Co., 1516-1524 N. Regester St., George R. Skillman, Proprietor.

So when the big, national baking interests had become the bad guy, George removed himself from that situation and started up another operation of his own. And look at how he’s marketing the new venture: “biscuits” and “crackers” in 1903 are products that are made almost exclusively in large commercial bakeries. “Bread” and “pie” are still primarily products that are made at home by most people. He’s trying to make this new business at least appear to not be a big, scary company.

Other than the damage to the Maryland Institute that I talked about in an earlier post, I don’t think George is personally affected by the Great Fire in 1904. All his properties are outside of the disaster area. He suffers a very personal disaster a few weeks later, though. On February 20 his wife Mary dies.

1905 is the last year that George is listed in the city directories as being the “proprietor” of the Skillman Bread & Pie Co., so it looks like his day-to-day involvement has slowed. Elmore B. Jeffery (who replaced George at National Biscuit Co.) is brought onboard as the Manager of Skillman Bread & Pie in 1906. How about that, huh? George has also left the family home on Myrtle St., and moved to 3617 Forest Park Ave (the current house on this site was built in 1920). I have to imagine that his wife’s death had something to do with both moves.

In 1909, George sued the Skillman Manufacturing Co., claiming that they owed him $115 and that the company was insolvent. He won himself the company receivership in the case, and the managers of the firm were forced to admit that George’s claims were true. At this point, the company address is listed as being 110 S. Charles St. The old Regester St. location was sold in 1910 for $14,000 to a man who built an auto repair shop there.

Skillman Bread & Pie Co. moves again to 104-112 W. Barre St. at least by 1912, and by 1914, it has completely disappeared from the city directories. It seems like the business had run its course.

George is back in The Sun in 1912, though. An article on November 19 states that he had sold the property at 203-211 N. Greene St. (somehow, he must have re-bought the place) to the Lexington Storage and Warehouse Co., and the next year’s city directory lists him as the President of that company.

The gig doesn’t last long, it seems. While he remains involved with the Board of Managers for the Maryland Institute, and as a Board Member for The Boys’ Home on Calvert and Pleasant St., by 1915, he no longer has an occupation listed in the directories. Sometime before 1917, he’s moved in with his daughter and son-in-law, George MacCubbin, at 3803 Clifton Ave (the current house at this address was built in 1910, so this seems to be the only house he lived in that still exists).

He died in that house, October 18, 1918 at the age of 81, having led a very full life.

He is buried at Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Baltimore.

The best indication of what he did is found in the 1917 edition of “A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents”. This collection of Presidential remarks also includes an “encyclopedic index”, there to give background information on a number of topics that may come up in speeches and letters of the Presidents. The entry in the index for “Baking Industry” explains that it has become at least the 12th largest industry in the country, and that the growth has been incredible in recent years. It specifically states:

Some of the other bakers engaged in interstate trade in the early history of the industry and who contributed to its national importance were…Skillman, of Baltimore….

Husband, father, baker, inventor, technologist, historian, businessman, civic leader, and “contributor of national importance”. George R. Skillman, my great-great-great-grandfather, was all of these things.

UPDATE – 12/27/2014:

I was able to find a display tin from the Skillman Universal Steam Bakery in an antique shop on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. My brother and I bought it to give to my father this Christmas so that it can stay in the family.

My Connection to the Great Fire

The roots of the Skillman family in the Baltimore area go back for several generations. In a way, my immediate family may not have learned about those roots had it not been for the events surrounding the Great Baltimore Fire that I wrote about yesterday.

Today, I want to tell that story.

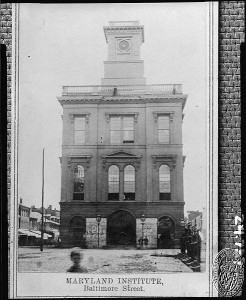

One of the buildings in Baltimore’s downtown business district back in the days before the fire was the Maryland Institute for the Promotion of the Mechanic Arts (which later became the Maryland Institute College of Art). Though the institution had been started in 1825, it had always rented space to hold its classes. The city block-sized building located between Baltimore and Water Streets, along the Jones Falls (the current site of the Port Discovery Children’s Museum), was constructed in 1851 and was the first structure that was purpose-built for the school.

In those days, the Maryland Institute was kind of half art school, half vo-tech. Courses in mechanics, chemistry, and drafting were taught alongside painting, sculpture, and music. There were different schools within the school, with night classes offered so that working people could improve their skills and get better jobs.

The building itself was quite spectacular. The bottom floor was a city market and the institute used the two upstairs floors. Along with classrooms and studios, there was a large meeting hall – one of the largest in the State of Maryland at the time – that was also used for public events. In fact, both the Whigs and the Democrats used the space for their party conventions in 1852.

The structure was in continuous use from the time it opened in 1851 until the very early morning of February 8, 1904 when the Great Baltimore Fire spread east toward the Jones Falls.

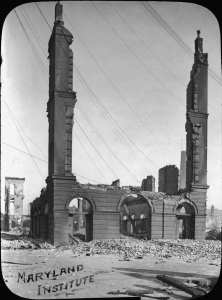

Being a relatively tall building for that part of town, embers that were blowing across town in the easterly wind hit the structure, and it soon caught fire – an isolated blaze at first that quickly spread to other buildings as firefighters were now facing a two-front battle.

No one knew it at the time of course, but the inferno was still more than 12 hours away from being under even moderate control. The Maryland Institute building didn’t stand a chance. Barely a shell remained once the fires were all totally extinguished a few days later.

Obviously, the institution has survived to the present day, and has morphed into a more pure fine art and design school. It’s also nowhere near the Inner Harbor anymore – its buildings now exist in the Mount Royal / Bolton Hill area. So what happened?

In the wake of the tragedy, the State of Maryland along with some wealthy benefactors and local business leaders, started looking for a way to rebuild. The mechanical and design skills that were taught at the school were extremely valuable to the local economy – especially when you consider the amount of re-building that a large part of the city was about to go through.

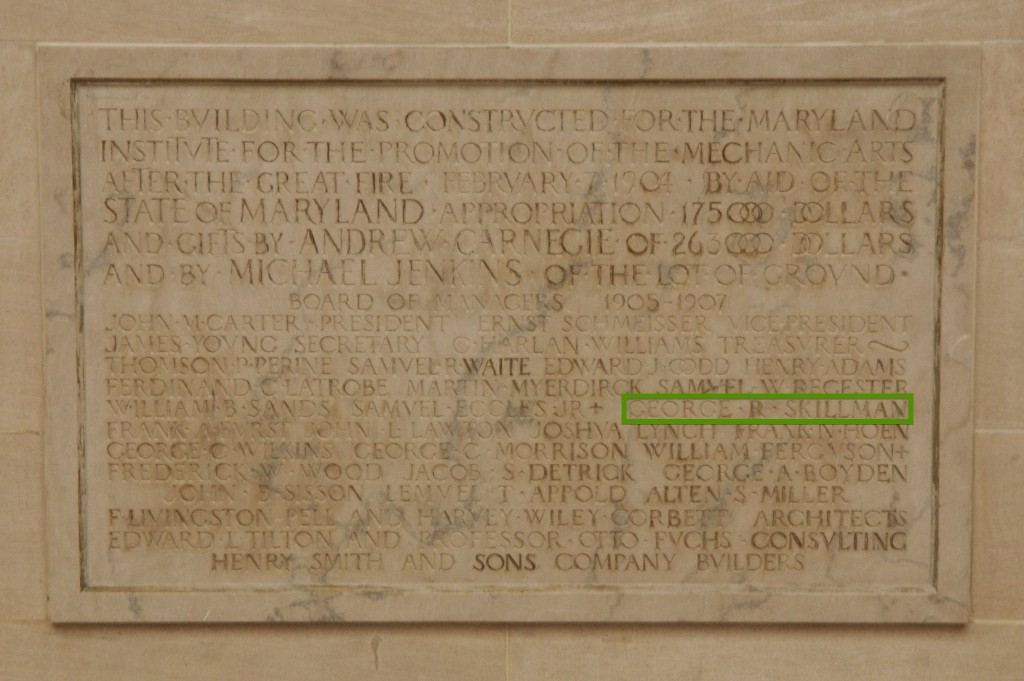

A plan to split the campus was devised. One piece of land in the Bolton Hill area was donated by Michael Jenkins to use as the site of a new building. Opened in 1908, this became (and remains today) MICA’s Main Building – housing the fine arts programs and even the first art museum in Baltimore. Another market building was constructed by the city at the original downtown site, and the institute’s drafting school would remain there – at least for a while.

So now, let’s fast-forward a few decades.

In the fall of 1977, my dad – George R. Skillman – started taking classes at the Maryland Institute College of Art. He’d always had an interest in history and architecture and those two subjects came together pretty perfectly in the aftermath of the Great Baltimore Fire. He had learned that MICA had been destroyed in the fire, and that the school he was attending was on the rebuilt campus. One day, his curiosity about that history led him to examine the dedication plaque for MICA’s Main Building.

The monument tells of the people who made the new building possible. Along with the monetary contributions of the State of Maryland and Andrew Carnegie, and the donation of the plot of land by Michael Jenkins, the school’s 1905-1907 Board of Managers – the men who oversaw the rebuilding process – were listed. Imagine how shocked my dad was to discover that his own name – complete with his middle initial – was there, carved into the wall:

Of course, this was obviously not referring to my dad. In 1908, his own father was still 13 years from being born. Who was this guy who had his name?

The accidental discovery spurred my dad to take an interest in our family tree. He started talking to relatives who had done research, and started to collect family records – a task that wasn’t as easy then as it is today. I’ve definitely benefitted from the stuff he found, and have also done some work to expand on it.

It turns out that this George R. Skillman wasn’t just a relative of ours, he was an ancestor: my great-great-great-grandfather. My dad is, at least indirectly, named for him. We don’t know as much about this forefather as we’d like to, but the few things that we know are pretty cool. He was the owner of a string of bakeries, and the inventor of a machine for making crackers. We’ve visited his gravesite, and the site of his largest bakery. We have some artifacts from his life – specifically some letterhead from his company. We also know that he must have done pretty well for himself to have served on the Board of Managers for such a large institution. My guess from looking at Census records is that the Civil War helped grow his business quite a bit.

My theme lately seems to be that history is all around us. I really believe that’s true. Deeply personal discoveries are there to be made if you keep your eyes open for them. Who knows? You may even find your name carved in stone somewhere.

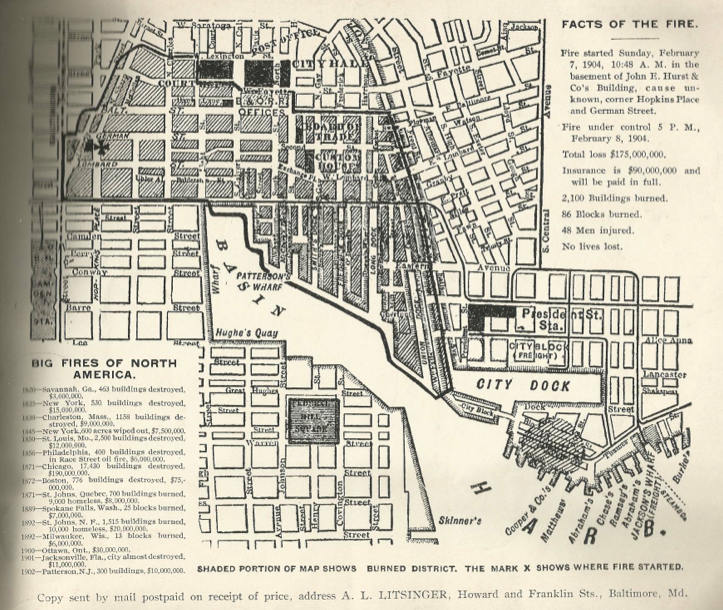

The Great Baltimore Fire

I was recently reminded that 110 years ago today, a horrific fire swept through downtown Baltimore near the inner harbor. It was the third-worst fire in American history, behind the 1871 Chicago fire, and the 1906 San Francisco earthquake/fire.

It started in the basement of the Hurst Building. Though we don’t know for sure, it may have been caused by a dropped cigar or cigarette left smoldering overnight among stacks of cotton fabric that were in storage there.

By the time firefighters arrived just before 11am, the blaze was already out-of-control. The building partially exploded, sending flaming debris flying onto adjacent structures. Strong winds from the southwest gusting up to 30 mph also helped spread the destruction. Within an hour, firefighters recognized the severity of the situation, and a distress call was put out for help from other fire departments, and they came from as far away as New York.

There was an early attempt to create a fire-break by blowing up the surrounding buildings with dynamite. The mayor endorsed this plan with the thought that it would save more property than it would destroy, but many of the buildings were too strong to collapse, and the additional explosions only served to create more fires.

It wasn’t until the fire reached the Jones Falls, and almost 1,700 firefighters had labored for nearly 2 days, that the fire was finally brought under control. In all, almost 1,500 buildings spread over 140 acres of the city’s central business district were completely destroyed. Estimated damages totaled perhaps as high as $175 million (roughly $4.4 billion in today’s dollars), with only about $32 million of that loss insured. As many as 35,000 people were put out of work by the disaster.

Despite all the destruction of property, the death toll was almost non-existent. Many sources report that there were no deaths as a result of the fire, but there was at least one badly burned body discovered in the harbor in the days following the event. Several first responders also suffered injuries that would eventually lead to their death, but all-in-all, the damage was much greater in economic terms than in human ones.

Amazingly, the city was able to (literally) rise from the ashes very quickly. Within 2 years, almost the entire area had been rebuilt using new city-wide fire codes, and more fire-resistant materials. Even in the wake of tragedy, Baltimore got to have a fresh start.

I first wrote about this local disaster a few months ago when I discovered a book about the fire among my grandfather’s things. I still have a PDF scan of the book available for people who want to see more photos of the destruction.

Update: A friend points out in the comments that there is a great animated map of the fire that gives more detail of how it spread. It’s definitely worth checking out. Thanks, Laura!

Update 2: My mother-in-law pointed out this wonderful collection of photos posted by the Baltimore Sun on the anniversary. I’d never seen a lot of these. Thanks, Karen!

The Historical Marker Database

Since I was a kid, I’ve loved road-side historical markers. I always wanted to stop and read them, and sometimes (when we weren’t in too much of a hurry) I got the chance to. There’s something really great about seeing tangible reminders of history out in the world where you’re living.

It turns out that I’m not the only person who feels this way. Several years ago, I discovered the Historical Marker Database – a hobby project of a history-loving IT guy like me – that seeks to catalogue every historical marker in the world. I make heavy use of the website when I’m researching, and it also makes for a fun way to go down a historical rabbit hole that I might not explore otherwise. You should definitely go check it out.

As you might imagine, finding all these markers is a huge undertaking – certainly more than one hobbyist can handle. A volunteer board of editors has sprung up over the years, and thousands of people have contributed photos and descriptions of markers to the cause.

When I was doing the research that resulted in my recent posts about the 138th PA along the Patapsco River, I discovered a marker that wasn’t listed on the HMDB website. I promptly registered for an account, read up on the editorial guidelines, and submitted an entry. People from all over the world can now discover the Mill Town History marker and learn a little bit about the town of Daniels, MD.

So be on the lookout for the history around you, and please share it with the rest of us!

138th Pennsylvania at Relay

Quite a few units rotated through duty at Baltimore – and specifically at Relay – during the war. The one that I want to focus on today is the 138th PA, which took up the post on August 30, 1862 and remained until June 16, 1863.

I mentioned before that Peter Thorn – the caretaker of Evergreen Cemetery in Gettysburg – left his family in August of 1862 to join the army. The unit that he joined went to Harrisburg and became Co. B of the 138th PA. Peter was selected to be a Corporal in the company. Another group of men formed in Adams County became Co. G in the 138th PA. After just a few days in Pennsylvania’s capital, the regiment shipped out to become part of the defenses of Baltimore, and was immediately assigned to duty at Relay House.

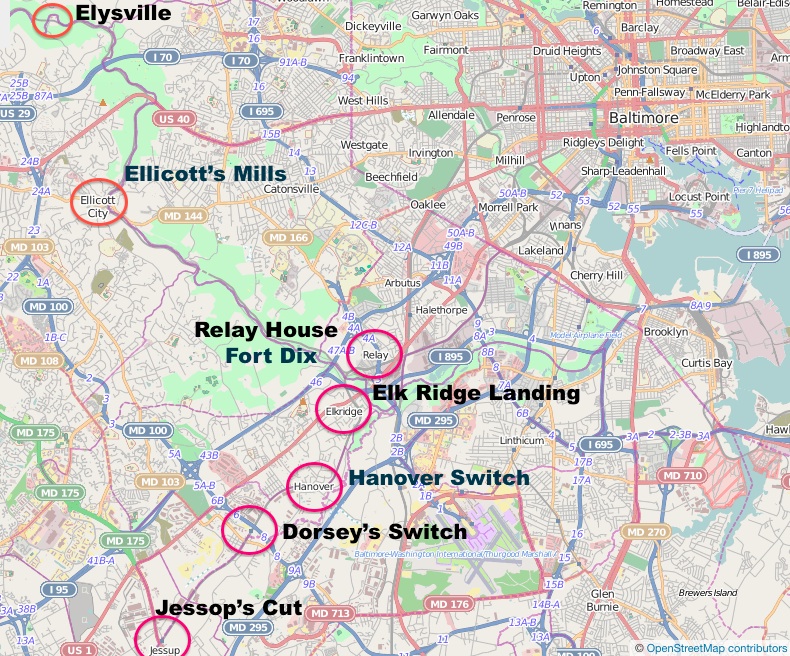

Col. Charles Sumwalt, commanding the 138th PA, initially deployed his men as follows (Adams County units bolded):

- Co. A – Jessop’s Cut

- Co. B – Ellicott’s Mills

- Co. C – Dorsey’s Switch

- Co. D – Elk Ridge Landing

- Co. E – Hanover Switch

- Co. F – Relay House

- Co. G – Fort Dix

- Co. H – Relay House

- Co. I – Relay House (with a detachment at Elysville)

- Co. K – Relay House

Some of these place names may seem a little off to locals. The spelling of “Jessop”, or the separation of “Elk Ridge” as two words, for example. “Ellicott’s Mills” is now known as Ellicott City. These things have evolved over time. “Elysville” is a place that no longer exists. It was a small mill town along the Patapsco river most recently called Daniels, but it was wiped-out in the flooding brought by Hurricane Agnes in 1972. As I explained in the previous post, Fort Dix was the temporary fortification constructed on the hill just above, and to the north of the Thomas Viaduct. It’s a little easier to understand if we put all these locations on a map:

You can see that the emphasis was on defending the Washington Branch – that’s where most of the troops were deployed.

Now, this isn’t to say that these assignments held through their entire duty in the area. Guard duty like this was a dreary task, and the units were routinely rotated back to the regiment’s headquarters at Relay House where there was a larger encampment that gave the men a chance to drill and practice their military skills. Relay House was also centrally-located in case reinforcements needed to be shifted along the railroad in a crisis. As I alluded-to before though, not much happened along this section of the B&O after May of 1861.

So what were these men spending their time doing? According to the orders of another unit that served at Relay, the 60th NY, the men were supposed to watch all the bridges, culverts, and switches along their sector. They were supposed to periodically patrol the track, looking for sections that had been removed or otherwise damaged, and for obstructions (natural or otherwise) that needed to be cleared. These tasks became even more important at night, when the cover of darkness meant that mischief was easier to pull off. This was not exactly a glamorous posting.

In fact, the task was so boring that Col. Sumwalt himself fell into a less-than-honorable lifestyle and was kicked out of the army for “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman” during the unit’s time at Relay.

At least for a little while though, Peter Thorn and the other men from Gettysburg were stationed practically right outside my front door, protecting the railroad that ran past Ellicott’s Mills. I spend so much time studying Gettysburg, and taking trips up there, that it’s funny to think that men from that little anonymous town spent more than 9 months of their Civil War service within a few miles of my house.

You never know what history might be lurking in your own front yard until you go looking for it.

The Occupation of Baltimore

Relay was secure. The railroad was firmly in Union control. The Winans Gun had been captured. Everything was going so well that Brig. General Benjamin Butler wasn’t at all concerned about an attack coming from Baltimore. In fact, he claimed that he’d yet to see:

…any force of Maryland secessionists that could not have been overcome with a large yellow dog.

That said, he wanted to take control of Baltimore and make sure that the secessionists couldn’t gain a foothold there. Without asking for permission from his superiors, he made a plan.

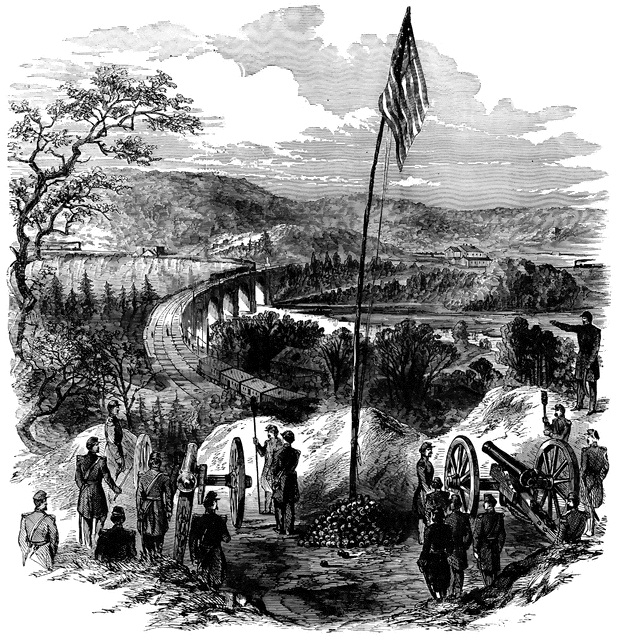

On May 13, 1861, under cover of darkness and in the midst of a heavy rainstorm, Butler loaded about 1,000 of his men onto a train at Relay and steamed into Baltimore. By midnight, they had possession of Federal Hill, and had begun building fortifications to hold the hill. It was a bloodless invasion as the rainy night had kept most of Baltimore’s citizens indoors and unaware of what was happening.

Butler notified the commander of Fort McHenry that the city was secure, but that guns should be trained on the downtown area, in case there was an attempt to take Federal Hill by force. None came.

Even though they were happy to have Baltimore neutralized, the higher-ups in the army didn’t like the blatant show of force. They immediately relieved Brig. General Butler of his command in Baltimore. New troops under Maj. General John A. Dix would be moved into town, taking possession of the forts around Baltimore and patrolling the railroads.

A new fort was constructed at Relay – on the hill directly to the north of the Thomas Viaduct – called Fort Dix, after the new commander. Camp Relay was established nearby, and Camp Essex sprang up on the Howard County side of the river in Elkridge. By the end of the war, there were 28 cannons in place to protect the Relay junction and the Thomas Viaduct. Thousands of troops served in the area, being constantly rotated in and out over the course of the war.

One of the units that spent a few months here was the 138th PA, and that will bring us back to Peter Thorn.

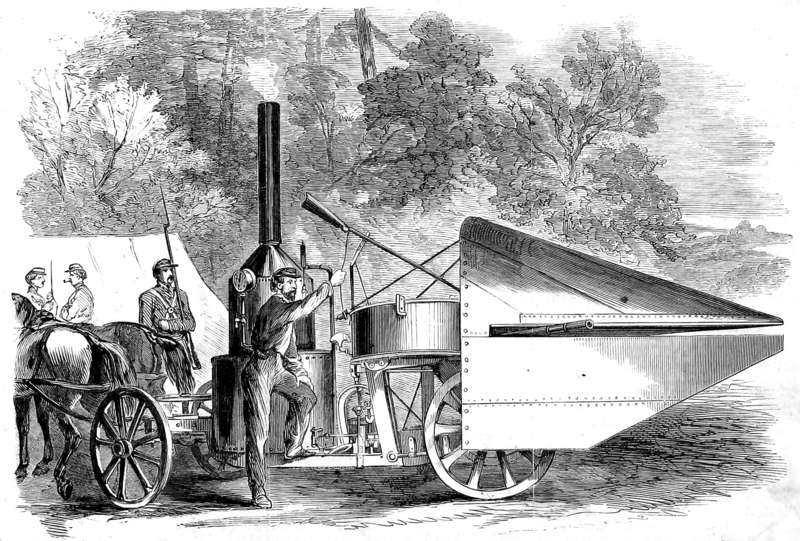

The Winans Steam Gun

After gaining control of the junction and bridge at Relay, Brig. General Butler got word that a new experimental weapon was being moved out of Baltimore – probably by horses along the old National Road (today known as Frederick Road, MD 144) – toward Harper’s Ferry with the plan of selling it to the Confederacy. This weapon was the Winans Steam Gun.

This was a steam-powered, self-propelled cannon that was capable of a very high rate of fire. No gunpowder was used – the balls were “fired” by the centrifugal force generated by a steam turbine. People who had seen it demonstrated in Baltimore prior to the war thought that it had great potential as a weapon against infantry and artillery. One observer wrote this in the Baltimore News after seeing a test firing:

Against a brick wall about a foot thick, heavy timbers, each a foot thick, were piled up. When finally placed ready for the test, there was about three feet of wood and one foot of brick ready to receive the discharge of the gun. The gun was some 30 or 40 feet away from the target. At a given signal an awful uproar was begun. In less than a minute the gun had been stopped. In that short time the heavy timbers had either been smashed or thrown into the air. Every one of us was convinced that the discharge would have mowed down a whole regiment.

Clearly, it would be a bad thing if this technology fell into enemy hands. On May 11, 1861, Butler halted the noon train from Baltimore to Ellicott’s Mills (present day Ellicott City) to commandeer it. As many as 500 men from the 6th MA, as well as 2 of Cook’s guns were quickly loaded on the train in the hopes of intercepting the experimental weapon.

The gun was in fact traveling along the Frederick Road in a mule-drawn wagon. Its smugglers were trying to disguise it as a piece of farming equipment in an attempt to avoid suspicion.

Butler’s efforts paid off. The Union troop train arrived just in time to stop the contraband in its tracks somewhere between Illchester and Ellicott’s Mills and the smugglers (including the gun’s probable inventor, Charles S. Dickinson) hardly put up a struggle. Four of them were immediately arrested. The weapon and prisoners were brought back to Relay.

The Union forces at Relay were very interested in testing-out their new capture, but found the results to be much less than what they expected. Aside from the issues they saw of how to keep the weapon properly fueled and loaded with ammunition in the midst of a battle situation, the performance of the gun was just pitiful. Rounds seemed to dribble out of the barrel haphazardly. It was hard to imagine this as a purported super weapon.

What these men did not know was that there was a second wagon traveling with the gun, and several of the important parts of the gun had been removed and placed in the other wagon prior to departing Baltimore. When the gun itself was captured, the second wagon escaped. The steam gun was useless to the Union forces, but in that, it also left the impression that the technology itself was flawed and further attempts to develop the weapon went nowhere.

Of course no one knew it at the time, but this was the most excitement that the area would see during the war. The B&O was too important not to be defended, and troops would rotate through this post until the end of the war, but the feared attacks never came.

In the next post, we’ll finally bring it back to Peter Thorn.

Securing Relay

In the last post, we looked at the Baltimore Riot that took place early in the war. To Union forces in 1861, Baltimore was hostile territory.

Not wanting a repeat of the experience that the 6th MA had, the next group of troops coming in from the north stopped at Perryville, MD and boarded boats. They were heading to Annapolis – using the Chesapeake Bay to route around the potentially-troublesome city of Baltimore.

These men were from the 8th MA, under the command of Brig. General Benjamin Butler. His orders were to open up the route into Washington, D.C. from the north so that troops and supplies could continue to flow.

Butler landed his men at the Naval Academy on April 21, 1861, and began the work of repairing the sabotaged railroads – first, the line leading from Annapolis to the Washington branch of the B&O at Annapolis Junction, and then the Washington branch itself. Once those lines were secured, Butler turned his attention to the north, taking possession of Relay – a very small town in the Patapsco river valley – on May 5, 1861 with the 6th MA, the 8th NY Militia, and Major Cook’s battery of Boston Light Artillery.

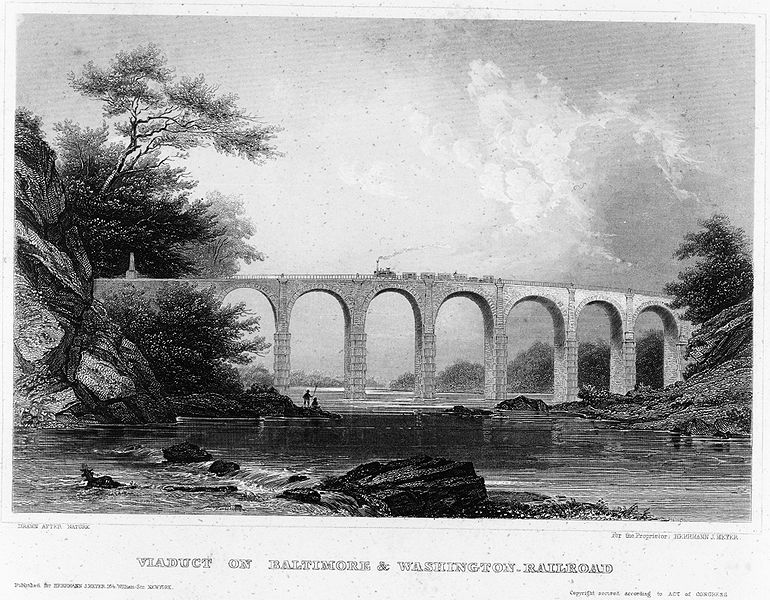

Relay was especially important because it is the northernmost point on the Washington branch of the B&O. It’s where the line began, and where it met with the main line from Baltimore to points west in the Ohio valley. And – most importantly – at the time of the Civil War, this was the ONLY railroad going into Washington, D.C.

In order for the Washington branch to be built in the first place, a bridge had to be constructed to cross the Patapsco river. That bridge is the Thomas Viaduct – named for the first President of the B&O railroad – and it remains the longest stone-arch bridge on a curve in the world, still carrying trains on their way to the capital to this day.

This bridge and the junction next to it were of extreme strategic importance to the Union cause. The army HAD to control this place, and being just 7 miles from Baltimore, it was facing real threats.

Butler placed his guns and deployed his 2,000 troops along the tracks in the area to ensure that no more sabotage could take place. All trains out of Baltimore were stopped and inspected to see if they were carrying men or materiel destined for the Confederacy, but this policy didn’t last long. At the request of the owners of the B&O, Butler agreed to back down somewhat and only perform random searches.

There will be one more exciting incident along the B&O, though. A tip about a secret Confederate weapon will cause some of Butler’s men to leave Relay to find and capture some potentially-threatening cargo.