History of My Office, Part II: Nike Missile Site BA-43

In my last entry, I explored the history of the plot of land where the office I work in is located. Today, we’re going to start looking at how some of the buildings on our campus came to be. But first, because I’m a fort nerd, let’s take a look at a little bit of the history of the defenses of Baltimore.

Probably the fort that immediately springs to everyone’s mind when you talk about Baltimore is Fort McHenry – focal point of the Battle of Baltimore. Located on Whetstone Point, it was completed in 1800, and was thought at that time to be placed so that it could effectively defend Baltimore from naval attack, and clearly it did in September of 1814.

As weapon technology improved and population expanded, it was decided that the defensive line would have to be moved farther out from the city in order to provide sufficient protection. This led to the construction of an artificial island off Sparrows Point that would become Fort Carroll. Even though it was never fully completed as designed (and it was never tested by an enemy) it served for a number of decades in the middle of the 19th century.

The grand march of technology continued on. By 1886, it was known that the coastal defenses of the United States were obsolete once again. New techniques involving smaller but more numerous gun emplacements, combined with naval mine fields became the preferred approach during the Endicott Period. Baltimore’s defenses were upgraded to this new system right around the turn of the 20th century. Fort Carroll was overhauled, and new installations – Fort Armistead, Fort Howard, and Fort Smallwood (just up the road from our campus) – were constructed. All of these were abandoned as defensive measures by the 1920s because of the arrival of another technological advance: military aircraft.

At first, this new threat was countered with the installation of several anti-aircraft gun batteries at strategic points around town, but when jets – and soon thereafter supersonic jets – came on the scene, it became clear that gun crews wouldn’t be able to shoot the new faster planes down. The Army began researching a different approach, leading to the creation of the world’s first operational surface-to-air missile: the Nike Ajax.

All through the 1950s and into the early 1960s, over 200 Nike sites were established in the U.S. to protect targets of military, government, or industrial value.

The system consisted of a few elements.

The missiles themselves were 38 feet long, with a two-stage rocket motor: the first being a solid fuel booster that would get the weapon off the ground and on the way to its top speed of over twice the speed of sound. Once fully airborne, the booster would drop off and a second sustainer engine would propel the missile to its target up to 30 miles away, delivering three powerful, high-explosive fragmentation warheads.

A ground tracking and control station (called Integrated Fire Control, or IFC) used three separate radars: one to search for incoming targets and determine whether they were friend or foe, one to lock-on to and track the intended target aircraft, and one to lock-on to and track the missile. With the locations of both the weapon and the target known, a ground-based computer (usually located in a semi-portable trailer) would calculate an intercept course and send guidance signals to the in-flight missile by radio. Once the missile was close enough, the detonation signal would be sent, sending flaming shrapnel ripping through the sky toward its target.

It is also important to note that the whole idea was that bombers wouldn’t ever make it to our shores (which of course they never did). If everything went according to plan, any incoming threat would be intercepted by Air Force or Navy fighters somewhere over the Atlantic. These Army missile installations only existed to be a last resort in case anything slipped through.

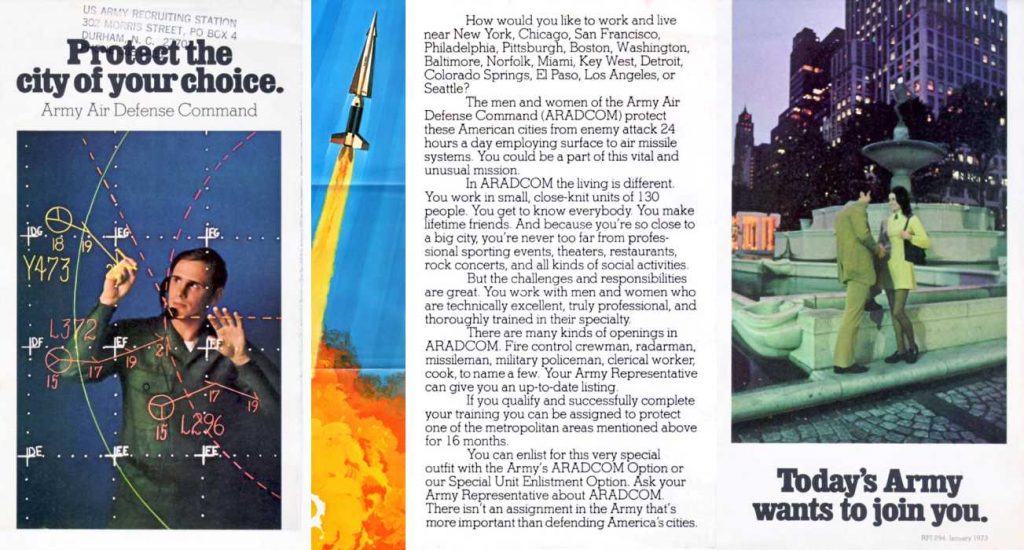

I wonder a bit about what it must have been like to serve on one of these bases. They’re very small, and the work is highly technical. I get a picture in my mind of a group of nerdy guys – what with all the computers, radars, and radios involved – sitting around waiting for doomsday to show up at the door. One of the most interesting things I’ve come across is a few of the recruiting materials for the Nike program. They really play up the idea that you can join the Army and serve in the U.S. near a big city (as opposed to, say, a jungle in southeast Asia). You can go to football games, and meet girls!

It must have been stressful for the local folks, too. I can imagine that having a missile base move in to your literal backyard would be quite unnerving. Community members had lots of concerns about housing for soldiers, danger from the missiles themselves (the potential for accidents, for example), where exactly these first-stage solid rocket boosters would be landing after they drop off, and even the possibility of their neighborhoods becoming targets of attackers or saboteurs. Luckily, the Army had answers for all of these concerns, and assured the locals that having a Nike site move in next door is really no more dangerous than having a gas station around the corner.

Meanwhile, the soldiers dressed like this for the missile fueling procedure:

Baltimore was included in the list of protected areas because of its manufacturing centers, port facilities, and proximity to Washington – in fact the Baltimore / Washington area was treated in many respects as one combined zone since the cities are so close together. Anne Arundel County hosted three installations: W-26 outside Annapolis near the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, W-25 near Davidsonville (both part of the Washington defenses), and our own BA-43 at Jacobsville (which was protecting Baltimore).

Our Jacobsville site came to be as the army was searching for “tactically suitable new base sites” around Baltimore, according to a January 5, 1955 article in the Baltimore Sun. By December, construction was underway on the facility that would one day become our offices.

The site seems quite large, but was only around 36 acres in total. Nike installations actually consisted of three sites: the IFC site, the Administration site, and the Launcher site. In the case of BA-43, the IFC and Administration sites were combined on one plot. The important thing was that the IFC and Launcher sites had to be separated by at least 1,000 yards because otherwise the missile-tracking radar wouldn’t be able to keep up with following the supersonic weapons as they launched vertically.

At this point, I should note that the grounds I’m describing here are school system property, and that they are treated as a secure facility – complete with fences, cameras, and various alarms. Please be respectful of those boundaries and don’t trespass.

Let’s have a closer look at each area. First the IFC / Admin:

Among the elements of the site that have remained relatively undisturbed are the concrete pads that the battery’s computer and radar trailers would have sat on:

On to the Launcher area:

Time has brought significant changes to both of BA-43’s sites. I’ll be detailing some of the reasoning behind that in a future post, but for now just know that these are very out-dated photos.

BA-43 was initially manned by the U.S. Army, Battery C of the 36th Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion from 1956 through September of 1958. A Captain, serving as the battery commander, would be the ranking officer on-site, with the full headquarters for the battalion – responsible for the Baltimore / Washington defense area – located at Fort Meade.

In September of 1958 things changed in the way that the Army wanted to categorize these types of units. In the resulting re-organization, BA-43’s garrison became known as Battery C of the 1st Battalion of the 562nd Air Defense Artillery Regiment. I think this change was due to bringing more sites online, and that a battalion-sized unit may not have been able to support the number of soldiers that were now in place in some of the larger defense areas like New York, Los Angeles, or Baltimore / Washington.

This arrangement remained in-place for BA-43 until 1960. The Army had started converting some of the bases to use the larger, faster, more powerful Nike Hercules missile (which sometimes even carried a nuclear payload). BA-43 didn’t make the switch to the new weapon. Instead, the Army decided to turn over the sites using the older style Nike Ajax to local National Guard units. This was done to save on some costs, as guardsmen could commute to the base and pack a lunch (removing much of the need for barracks and mess facilities). In March of 1960, BA-43 was turned over to Battery A of the 1st Battalion of the 70th Air Defense Artillery Regiment, Maryland National Guard. This unit would be in control of the site until it was shut down in December of 1962.

I’m pleased to report that the weapons of BA-43 never had to be used against an enemy. As the 1970s approached, the threat from Soviet bombers became superseded by the threat from Soviet ICBMs, and while an attempt was made to create an anti-ICBM Nike missile (the Zeus), it was ultimately decided to end the Nike program in 1974.

I started this post with a brief overview of the history of Baltimore’s defenses because I think that here we have a great illustration of the incredible progression of technological advancement in the 20th century. Fort Smallwood – just at the tip of the peninsula – was completed in 1905, and was thought at that time to be positioned to provide an adequate defense of Baltimore. By 1927, it was abandoned because it was made obsolete by new technology. Thirty years later, the land just 2 miles south of Fort Smallwood – the place where BA-43 was constructed – was only useful defensively as a last resort. Within 6 years, that purpose was even made obsolete. It’s a remarkable pace of change.

In the next post in the series, we’ll find out what became of BA-43 once the Army had abandoned the site. For now though, I’ll end this post with another video. This one is from an Army-produced film highlighting some aspects of life at the Nike site near Upper Marlboro, MD. It’s a pretty interesting piece:

Here are some useful sources that I consulted for general information in putting together this post:

- “Rings of Supersonic Steel, Third Edition” by Mark L. Morgan and Mark A. Berhow, Hole in the Head Press, 2010

- Ed Thelan’s Nike Missile Website – An amazing wealth of information on the Nike program. It’s easy to get lost exploring all the resources he’s collected.

- The Nike Historical Society – Another great site with lots of stories from Nike program veterans.

Thanks for the interesting read! I grew up very close to BA-43 and attended the school that was opened after BA-43 closed.

Jane, What school?

What school are you referring to?

Ft. Smallwood Elementary School. The back building was for 4th graders. The main building (near Ft. Smallwood Rd.) was for 5th & 6th graders. I went there from 1967 to 1968 (4th grade) and from 1968 to 1970 (5th & 6th grade). After 6th grade we went to George Fox Junior High School from 7th to 9th grade and then to Northeast High School 10th to 12th.